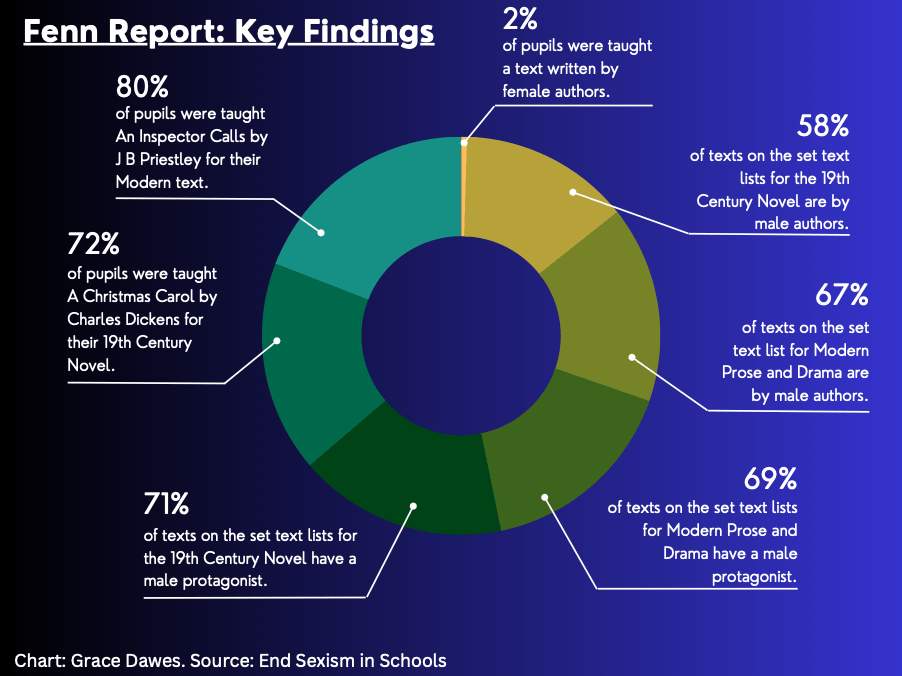

Teachers blame underfunding and the national curriculum for shocking data that was released last month, showing that only 2% of GCSE students study a book written by a female author.

The report by Rachel Fenn with End Sexism in Schools (ESIS) showed that GCSE set texts, specifically those commonly studied by students, are significantly more likely to have male authors and protagonists than female equivalents.

Fenn’s key findings, as she put it, “unequivocally evidences the invisibility of women in the curriculum”. But she adds there is more at play than just the lack of female representation; the shocking data has also been influenced by the ways in which schools teach the texts and how the texts treat women.

The report set out to analyse the GCSE set texts lists with a focus on the representation of female authors and female characters.

GCSE set texts are informed by the national curriculum and are represented by four main awarding bodies: AQA, OCR, Eduqas, and Pearson Edexcel. Some of the most popular texts within these bodies, that are studied at A-Level, include: An Inspector Calls by J B Priestley, Lord of the Flies by William Golding, and Blood Brothers by Willy Russell. All notably are penned by male authors and include male protagonists.

A mandate to balance the books

The key findings of the ESIS report are represented here:

The report based its findings on all awarding bodies that were able to provide data of the number of pupils who answered each text in GCSE examinations in 2018, 2019 and 2022 (all were able to provide data apart from Pearson Edexcel).

In total, 20 different texts make up the set lists for Modern Prose and Drama and 9 texts for the 19th Century Novel text list.

Fenn’s headline figure that 2% of pupils were taught a text written by a female author has been commented on by Victoria Elliott, an Associate Professor of English and Literacy Education at the University of Oxford.

Elliott said: “The headline figure ‘2%’ is inaccurate – it only applies to the modern texts, and Fenn’s own data shows a 3% answer on a woman for the 19th century novel. But even so, a maximum of 5% is absolutely horrifying.”

Why is this happening?

In her report, Fenn summarises three main contributing factors were a lack of options to study female authors, a lack of take up by teachers of the female authored texts provided, and the problematic representation of women in the choice of texts.

Alice Sharman, an ex-secondary English teacher and Head of Department from Cheshire, attributes a lack of options to the former education secretary. She said: “When Michael Gove brought in the new curriculum, a lot of people were expecting a year for there to be a big modern overhaul to the curriculum.

“But Michael Gove’s curriculum was really old-fashioned, and that is when we got this prioritisation of knowledge and learning off-by-heart rather than skills which the previous curriculum was based on,” said Sharman.

She explained that Gove’s reform had praise for tradition and the male literary canon, which in turn centralised the exam board’s choices for their text lists.

Plans for the new national curriculum were unveiled by Gove in 2013, removing celebrated books such as To Kill a Mockingbird and Of Mice and Men. Authors from Commonwealth countries were also eliminated from text lists, such as Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s A Purple Hibiscus, Lloyd Jones’s Mister Pip and Doris Pilkington’s Rabbit-proof Fence.

Some new titles that appeared in the new curriculum included An Inspector Calls by J B Priestley, The Sign of Four by Arthur Conan Doyle, and DNA by Dennis Kelly.

In particular, female texts which appeared on the new curriculum were: Anita and Me by Meera Syal, the only modern novel with a female protagonist on the set text list of all awarding bodies (AQA, OCR, Eduqas, and Pearson Edexcel), My Mother Said I Never Should by Charlotte Keatley (OCR), Never Let Me Go by Kazuo Ishiguro (OCR, Eduqas, AQA), A Taste of Honey by Shelagh Delaney (AQA, Eduqas) and Oranges are Not the Only Fruit by Jeannette Winterson (Eduqas).

However, Fenn explained in her report that the choice of female texts included in the new curriculum were particularly lengthy in comparison to male authored texts that were “considerably shorter”.

Fenn said: “(This) means that the female authored texts are not equally matched in terms of teachability and accessibility to the male authored choices.”

Sharman believes this has been a factor in the normalisation of fewer female-authored texts in classrooms. “Curriculum leaders are under so much pressure with their day-to-day workloads, they don’t necessarily get the opportunity to redesign the curriculum. If you have a head of English who has been there for a long time, they’re not going to mess with what’s already working for them,” she says.

“As a school, you have to buy in sets of books, and schools are so chronically underfunded at the moment that they haven’t got the budget to do it.”

Sharman explained that teachers already have their PowerPoints, knowledge, and annotated copies that have worked well in classrooms for years and continuously gets them good results, hence why they choose to stick with them.

Elliott concurred that funding was a contributing factor and said: “Schools now can’t afford to give books to students to take home to read in case they lose them. So, all the reading must be done during lessons, giving an advantage to the shorter texts.”

Why does this need to change?

The lack of female authorship is not the only troubling conclusion from Fenn’s data, however. It has been claimed that female representation is not only limited by the marginalised number of female writers, but also by the limited number of female protagonists in the set texts.

Elliott said: “There is a real benefit to reading a whole range of texts that show you the viewpoints of all sorts of different people. In particular, it is really valuable for students to see people who don’t look like themselves being the protagonists at the centre of a story.

“At the moment, if you’re a middle-class white boy in school, as far as you’re concerned, all the stories are about you. That is really important in thinking about the future and how they react and respond to other people and in life.”

Victoria Elliott

The report by Fenn highlighted the discrepancy between the number of female protagonists compared to that of male on the set text lists. The data showed that 71% of texts on set lists for the 19th Century Novel have a male protagonist and 69% of texts on the set text lists for Modern Prose and Drama have a male protagonist.

Fenn commented that this is an important factor to the representation of women in set texts: “After all, it is the characters and not the authors that pupils will spend most time discussing in lessons.

“By only providing the option for pupils to engage with male perspectives on the world in the literature they read, not only do boys never learn to empathise with and appreciate the viewpoints and experiences of women, but they also receive the clear message that women’s voices and perspectives are less important and less valid.”

The report found that this is suggestive of a bias towards the teaching of texts with a male protagonist as perhaps because of a popular belief amongst teachers that boys will only read books with male protagonists, but girls will read books with a protagonist of either gender.

Sharman said: “There is a real fear within the teaching community that if you teach female authors, boys will be disengaged and it really, really annoyed me that there wasn’t a consideration the other way, or equally that we were doing boys this great disservice by making them study female texts.”