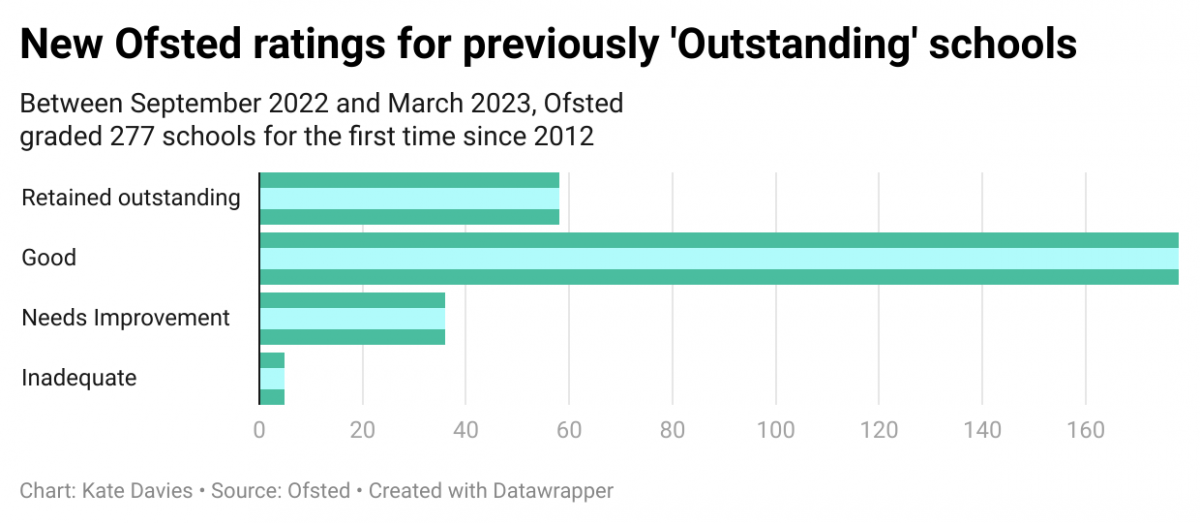

Almost 200 schools across England have been downgraded from Ofsted’s highest rating since September after receiving their first inspections in more than 12 years.

The regulatory body has graded 277 schools so far this school year, but only 20% have maintained the ‘outstanding’ rating they received before 2012. According to Ofsted, these figures show the need for regular inspection to provide a “constructive challenge.” However, some teachers say there is more to the data.

Alice Sharman, a former head of English from Devon, taught for 10 years. She said: “There’s a whole lot more to why ratings have dropped. Ofsted constantly move the goal posts, so people don’t really know what they want.”

In 2019, Ofsted released new inspection arrangements which Sharman says made it even more difficult for schools to be ‘outstanding’. She says previously ‘outstanding’ schools are “fundamentally the same” but the new inspection framework does not reflect this.

The changes were intended to focus inspections on what children learn rather than results, which Ofsted say discourages a culture of teaching to the test. However, Sharman says inspectors still place too much value on data and they need to have more humanity.

“There is a place in education for a regulatory body but there should be some shades of grey or they might as well make some AI [Artificial Intelligence] software to crunch the data,” says Sharman.

Inspection exemption implemented by Michael Gove

Former education secretary Michael Gove implemented an exemption in 2012 that meant routine inspections would not take place in ‘outstanding’ schools. This applied whether or not the school opted to become an academy.

It meant 600 secondary schools, 2,000 primary schools and 300 special schools would only be inspected if there were specific concerns. The exemption was lifted in 2020 but that has left thousands of schools whose last inspection was, on average, 13 years ago. For some, it has been 15 years, Ofsted reports.

Since 2020, Ofsted estimates it has inspected 1,136 previously ‘outstanding’ schools. Of the portion of inspections which were graded, around 81% have changed ratings. The latest data from this year’s inspections builds on a series of reports that most inspections have downgraded schools.

Ofsted Chief Inspector Amanda Spielman said the exemption policy was founded on the hope that high standards would not drop once they were reached. She said: “These outcomes show that removing a school from scrutiny does not make it better.”

According to Ofsted, all previously exempt schools will be inspected by July 2025.

Ofsted facing criticism

The watchdog has come under fire in recent months, with many teachers speaking out against the pressure Ofsted visits puts teachers under.

In January, headteacher Ruth Perry committed suicide after she was told her school would be downgraded from ‘outstanding’ to the lowest Ofsted grading of ‘inadequate’, her family reported. Perry had worked at Caversham primary school in Reading for 13 years.

Spielman responded to the criticism, saying: “Ruth Perry’s death was a tragedy. The news of her death was met with great sadness at Ofsted.”

Headteachers have since called for the inspectorate to overhaul its methods, including removing the grading system which places schools into one of only four categories. One headteacher has since refused entry to Ofsted inspectors and posted her plan on Twitter.

Sharman says the system does not allow for the different circumstances that the education system exists within.

“Painting every school with a broad brushstroke stops anyone getting to the heart of a school’s problem. What are they supposed to do once they’ve been slapped with this general judgement?” says Sharman.

She adds that Ofsted need to be more supportive after the inspections. The structure that Ofsted follows means inspectors spend two days at a school before making their final judgements and awarding a grading.

Afterwards, the final report is published on the Ofsted reports website within 38 days. Schools are also required to supply the report to all parents of pupils at the school.

“There is no sit down with strategies or aims of how to achieve the improvements they want. Where is the support?” Sharman adds.

Emma*, a teacher who asked to remain anonymous, experienced Ofsted as a trainee and says she saw the impact impending inspections have on schools. Emma said: “It’s a bit of a threat that hangs in the air. Someone would say we needed to do something because Ofsted liked it, but it doesn’t feel like much thought went into whether it’s a good thing.

“My children were at the school when it was inspected and still remember it.”

Lack of funding causing standards to drop

In October, a survey by the Association of School and College Leaders found 98% of schools would have to make cuts to meet rising energy bills and inflation. It also found over half were expecting to reduce staff and increase class sizes in a bid to save money.

Sharman recalls funding cuts to her school meant she lost several hours a fortnight which she would have used to mark books and plan lessons. “That’s where funding really has an impact – on the number of hours teachers get to do their job outside of teaching classes,” says Sharman.

Eligible schools had been receiving help with energy bills from the UK governments Energy Bill Relief Scheme, but the support ended on April 1.

How can Ofsted improve?

Once Emma’s school was given an ‘outstanding’ rating, she said it felt like a “huge sigh of relief” to be exempt from inspections. However, she added that grading is not a clear-cut process.

“Inspections are quite subjective so you could be ‘outstanding’ one day and ‘good’ the next.”

The NAHT School Leaders Union wants the watchdog to pause inspections so a review to cut the risk of harm to school staff can take place. Spielman has met senior NAHT representatives, but no agreements have been reported.

Emma says the inspections minimise complacency and should still exist. However, they argue some changes would benefit staff and students.

“Isn’t it enough to be ‘good’? Then there would be slightly less pressure to always be better,” Emma says, “it would be nice to feel like someone was checking in with you rather than checking up on you.”

In the UK, anyone feeling emotionally distressed or suicidal can contact Samaritans by calling 116 123 or emailing jo@samaritans.org

*Names changed upon request