It has been an exciting few weeks. First Pfizer announced a 90 per cent efficacy of its vaccine candidate, then Moderna one-upped it with 94 per cent. Then, in the early hours of Monday morning, November 23, the Oxford vaccine was shown to have 70 per cent effectiveness – increasing to 90 if people were given an initial half dose followed by a booster. The Oxford vaccine also has the advantage of being by far the cheapest and easiest to store of the three.

Scientists say that an approved vaccine would carry little risk, but people are nervous nonetheless.

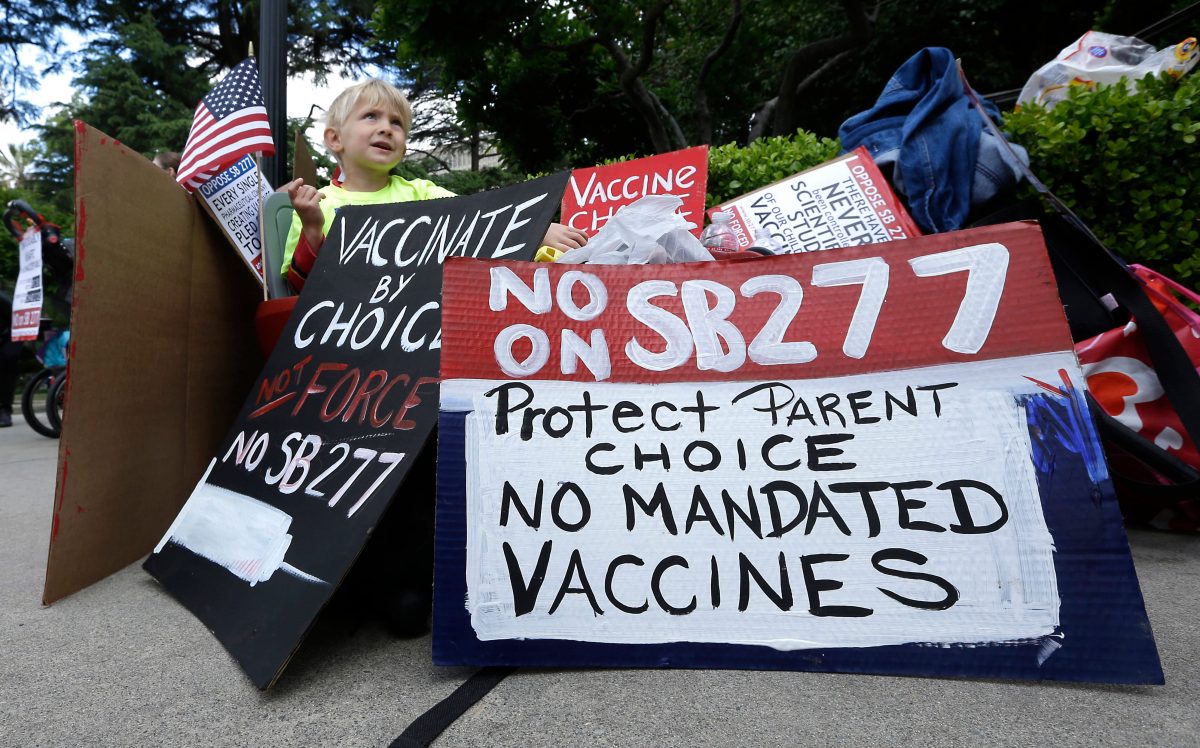

The vaccine intention for UK residents is difficult to pin down when there is not a confirmed vaccine. But a report by the British Academy and the Royal Society for the SET-C (Science in Emergencies Tasking – Covid-19) Group found that 36 per cent were either uncertain or very unlikely to get vaccinated against coronavirus. With an estimated 70-80 per cent take up necessary to achieve herd immunity, this could be a problem.

Why are people nervous about a vaccine?

Why is it happening so fast?

One of the most commonly cited reasons for unease about a coronavirus vaccine is time.

“In general, I have no problem with vaccines – I’m in favour of them,” said Kim, a Kingston resident. “But it’s just this one I’m on the fence about… I can’t quite fathom how they would’ve got a vaccine up and running this quickly.”

In the past vaccines have taken anything from two to 20 years to develop, owing to a comprehensive process involving pre-trial research and three phases of trials on humans with varying numbers and types of participants.

News of a potential vaccine less than a year since coronavirus first appeared in Wuhan is therefore alarming for some, with fears that the usual processes and safety checks have been rushed or skipped entirely.

But William Budd, a Clinical Research Doctor at Imperial College who has been involved in several trials including for the Oxford vaccine, says that the speedy development is not what it might seem.

“I understand the concern about speed entirely… but there are a lot of reasons why it’s quicker [than usual],” said Budd. “I don’t think I’ve known every country in the world work on the same vaccine.”

He said the amount of money being pumped into vaccine research is huge, and that the concentration of research on a single goal enables the trials to happen much faster, as the necessary technology is not being used in any other research.

“Also, coronavirus is very closely related to previous infections like MERS… and Oxford was actually already developing a MERS vaccine,” said Budd.

He said that although the vaccine was not needed in the end, because MERS went away on its own, the existence of previous research enabled rapid development of a coronavirus vaccine candidate.

He also explained that getting the necessary number of participants was also a common reason for delays, which has not been a problem with coronavirus vaccines because of a collective drive, from both researchers and members of the public, to defeat the virus.

“There’s been no change in the process of the trials,” said Budd.

What are the side effects?

Another common reason for concern is the potential for side effects. None of the three main candidates have reported any serious side effects, but nevertheless, some people are worried.

Nikki Simmons, another Kingston resident, has transverse myelitis, a rare neurological condition where the body’s immune system mistakenly attacks the spinal cord. Often there is no obvious cause, but it can follow viral or bacterial infections, and is also associated with other disorders such as Multiple Sclerosis. Very rarely it can appear following vaccination, for example for hepatitis B or MMR.

In September the Oxford vaccine trial was paused after a participant developed transverse myelitis. Whilst the trial has since restarted, Simmons is wary of vaccines that use adenoviruses, the technology used by the Oxford vaccine.

“I’m the sort of person that believes in science. So I’ve never had an issue with vaccines in the past at all, I’ve always had no problem getting all my jabs,” said Simmons. “But I believe that I was susceptible to transverse myelitis… I’ve been neurologically affected once and I don’t want it to happen again.”

Simmons is concerned that because of pressure to roll out a vaccine quickly, the case might not have been properly examined.

“Because we haven’t been given much information – they’ve been very cagey with their press release – it concerns me that perhaps they haven’t fully looked into it,” she said.

The trial was in Phase Three of human trials when it was paused, which is when the vaccine is tested on thousands of people – in the case of the Oxford vaccine, 20,000 people in the UK and Brazil. Because of the number of people given the vaccine, it is not uncommon for participant illness to cause trials in this stage to be paused.

Budd stressed that, although the need for patient confidentiality prevents the release of much information, the suspension of the trial was unlikely to be a cause for concern.

“Transverse myelitis, although unusual, does happen as a percentage of the population if you vaccinate enough people,” he explained.

“Sometimes you don’t know the cause of something but you can prove it’s not linked to something else, which is very common in medicine.”

He said that when a trial participant experiences a so-called “adverse event”, the trial must be paused to allow for investigation even if there’s no reason to believe it was a result of the vaccine.

“For instance, if you gave someone an injection [in their left arm] and then on their right they had a rash, it’s unlikely to be linked… but you still need to report it as an adverse event.”

He said that the pausing of the Oxford trial demonstrates the rigid safety protocol in place, and that the subsequent unpausing means there’s no reason to believe the case of transverse myelitis was caused by the vaccine.

“They wouldn’t have restarted the trial unless they could show there wasn’t a link to it,” he said. “They must have come to the conclusion that it wasn’t linked, and that’s obviously backed up by the health regulator agency.”

Budd also pointed out that there have been cases of transverse myelitis in participants who receive placebos in coronavirus vaccine trials – existing vaccines or substances with no effects, given to half of the participants to compare the vaccine group against. The Oxford trial is a double-blind, which means neither participants nor doctors currently know who has been given which jab.

In terms of other side effects, the participants in the trial have been closely monitored.

Lois Clay Baker is a final year medical student on placement at Kingston Hospital. She is also a participant in the Oxford vaccine trial, having received her first jab in May and a booster at the beginning of this month.

“[After they administered the vaccine] they did some blood tests and kept me in for about half an hour just to make sure my vitals were ok,” she said. “At first, I had to take my temperature every day and keep a symptom log… and then after that, you do a weekly [symptom] survey.”

She said that in the six months since she received the first dose she has had no symptoms, but if she had done then she would have known exactly who to alert.

“It’s scary going into something that you know has only been tested on a few people… but I trusted what they were saying,” said Clay Baker. “If you’re worried then your GP or pharmacist is the person to talk to… it’s ok to have doubts about [the vaccine] but make sure you’re speaking to someone reliable.”

Is it safe for everyone?

There is also concern about whether a vaccine will be safe for everyone.

Simmons said that, as well as people who have a history of neurological conditions, she would also be wary of the effects of the vaccine on people with compromised immune systems.

Budd, who himself is immunocompromised, said that after vaccine efficacy had been established for the general population, there would be studies on specific groups of people with particular needs and medical histories.

But he also said that the risks of vaccines on the immunocompromised are often not what people think.

“The issue in terms of vaccines and the immunocompromised isn’t that it will cause illness, it’s that the immunocompromised won’t get such a big immune response,” he explained. “So they’ll be testing to see if the doses need to be increased [in order to make that person immune].”

As well as varying medical histories, there are other things that research will take into account.

“The earlier phases were limited to [healthy] 18-45-year-olds,” said Budd. “But they’re now using 18-75-year-olds, and some of them will have underlying conditions.”

The trials also use participants from varying ethnic backgrounds – Pfizer is an American company but 42 per cent of its 43,538 participants were described as being from “diverse backgrounds”, and the Oxford vaccine has been administered to participants in Brazil and South Africa as well as the UK. It recently issued a call for more British participants belonging to ethnic minorities to further increase the diversity of their research.

So can we trust a coronavirus vaccine?

In short, if a vaccine makes it through the regulatory process, there is no reason not to trust it.

The protocols in place for regulating and developing vaccines remain unchanged where it matters. Initial research might have focussed on other coronaviruses and researchers may be able to recruit participants much faster than usual. But the rigid 3-phase human trials and the necessary approval from regulatory bodies have not been compromised by the urgent need for this vaccine to be a success.

Why does trust matter?

Trust matters because, for a vaccine to be successful in stopping disease, there must be a mass desire to get it.

The current estimates of people who intend to get the vaccine are right on the cusp of the necessary number. Any lower than this threshold and the revered herd immunity will not be reached, but we cannot social distance forever. So then what happens?

“The number of deaths would be astronomical in the vulnerable if you reduced lockdown measures [without a vaccine],” said Budd. “There are two ways to stop pandemics – there’s getting a sufficient treatment… or a vaccine.”

Of the two, a vaccine is infinitely preferable. Not only does it stop people getting sick and therefore protect them from the long-term effects of Covid that are only just becoming apparent, but it also eliminates the risk of overwhelming the NHS, leaving it free to continue providing treatment for other things like cancer.

In reality, a vaccine is the best way out.

So what can we do?

Public trust is the key to a vaccine’s success, so what can be done to earn it?

“Transparency,” said Simmons. “I think that would make me feel a lot more comfortable – I’d possibly even go for an adenovirus [vaccine] with more transparency.”

Simmons said that if scientists were more open about their research – and in particular about investigations into “adverse events” – she would find it easier to trust the outcome.

Kim agreed. “I’m sure there’s medical studies and scientific studies that we don’t get to see,” she said. “If someone explained to the general public in layman’s terms so that we understand that it has been rigorously tested across all kinds of people, then maybe I might feel more comfortable.”

Budd came to the same conclusion – and so he has made it his mission to communicate information about coronavirus and the various vaccine candidates to the public in accessible, easy-to-understand ways. His TikTok, which he uses to explain how the vaccines work as well as to share amusing videos about his experience of the pandemic, has over 700 followers.

He also works with Team Halo, a UN initiative aimed to tackle “vaccine hesitancy”, that also uses TikTok as one of its main platforms.

“You fear something that you don’t understand, which is understandable especially if it’s very scientific and you haven’t got that background,” said Budd.

“People are nervous about the vaccine, and that’s not a problem, you can be nervous about any drug you take. But how low the uptake is will be worrying in terms of… will it never get to the point where you vaccinate enough people?

“I think there needs to be more education. I think people need to be explained in layman’s terms how it works.”

For more information about vaccines from Team Halo, follow them on Twitter or visit their TikTok.