Among deer and dog walkers, there is one sight that has become part of the furniture in Kingston’s Bushy Park. Embark on a stroll through London’s second-largest royal park – spanning 1,099 acres to be exact – and you will no doubt encounter the garish orange glow of the Bushy Park ranger jacket.

“I was quite keen on the orange,” says Anne Scoggins, a semi-retired clinical project leader and one of the park’s 60 volunteer rangers.

With festivals postponed and holidays cancelled due to Covid, parks became the saving grace of our summer, the home to our six-man birthday bashes and endearing first dates. We watched the shamrock greenery become sun-scorched terrain in a year that offered little else. Now, the leaves around us have freshly fallen, crisp and tinged with gold. Autumn has settled.

“I think a lot of the whole population have discovered parks really during Covid as a place to be, that you’re allowed to be,” Scoggins says.

A survey by Natural England found that in August, nearly 70 per cent of adults had spent time in green spaces in the previous two weeks. Almost 85 per cent said being in nature made them happy.

Our parks have meant more to us this year than ever before, and the Bushy Park rangers are on hand to make sure this local haven is as accessible and beneficial as possible.

When I meet Scoggins next to one of the park’s many large ponds, on an unusually mild and bright November afternoon, she has just finished her weekly patrol. In her two-hour time slot, she has been educating visitors on how to enjoy the park with care, and preserve its vibrant ecosystems.

“There’s a lot of stuff to do with the ecology of it,” Scoggins says. “It’s a balance of keeping the natural environment, but also you want humans to come in as well, you don’t want to lock them out.”

In 2015, the park was acknowledged as a Site of Special Scientific Interest by Natural England, due to its spectacular population of threatened invertebrates, ancient trees and other wildlife. Protecting it is the rangers’ top priority.

Scoggins, who lives in Hampton, has been a volunteer ranger since March; after her first training session, Covid hit, and the park rangers were sent home. She left her role at a pharmaceutical company in July after 15 years and got back out in the park in August.

“I just thought I do not want to go back to sitting in an office, I want to get out and just enjoy the outside, nature. So I stopped working,” she tells me. It is personal too: her son attended local Bushy Tails nursery, and they would walk through the park to the nursery every day.

“It’s been part of our lives all the way through,” she says.

Rise in visitor numbers started before Covid

Back out and on patrol, Scoggins has seen firsthand how much people are appreciating the park. In recent weeks, she has spoken to up to 90 people in her two-hour time slot.

Though hard to be precise, visitor numbers have indeed increased this year. But Bushy Park’s popularity was on the rise long before the pandemic hit.

Jo Haywood, volunteer ranger coordinator at the park, says social media has caused visitor figures to skyrocket; at last count in 2014, there were 2.4 million visitors to Bushy Park every year, double the amount in 2008. This figure could be as high as six million now, Haywood says.

This was one of the driving forces behind bringing volunteer rangers into the parks in early 2019, to help manage the exponential rise in visitors and ensure the wildlife, including the park’s 300 plus red and fallow deer, are kept safe.

“People see the photos, and they think ‘actually that looks really nice, and it’s on our doorstop, so let’s go as well,” Haywood says. It has been both a blessing and a curse.

While the parks are open for all to appreciate, there is no doubt that rising footfall has put pressure on the wildlife – particularly the deer herds.

Members of the public must stay away from the deer

From September through to November it is mating season; stags are flooded with testosterone and lock antlers with one another, bellowing and facing off to protect the hinds in their harem. People, especially photographers, flock from across the country to witness one of nature’s finest spectacles.

The deer have dominated Scoggins’ conversations. “For the last six weeks, up until this week really, it’s been mainly managing interactions with people and deer,” she explains.

The Royal Parks urge people to stay at least 50 metres away from the deer, particularly during rutting and birthing seasons. They are, after all, wild animals; their temperament is unpredictable. As Richmond Park’s retired gamekeeper of 30 years, John Bartram, once said: “You wouldn’t walk up to a tiger and pat it on the head. Why would you want to get next to a deer that’s got twenty spikes sitting on his head?”

Scoggins and I speak for just two minutes before a man has to be told to step back from a stag nearby, foraging for food. Through the course of our 45-minute chat, half a dozen others try their luck, creeping as close as possible to him. Just this week, the Royal Parks again pleaded with visitors to keep their distance, after a photo was shared on Twitter of a man appearing to be attacked by a deer in Richmond Park.

“I think lots of people think ‘oh, aren’t they really cute’, and actually it’s like, no,” Haywood says, bewildered.

The deer are no Bambi – they are unpredictable

Social media has painted the deer as tame and unfazed, zapped straight out of a Disney film. “The problem with social media is that it shows how nice they look, but there’s no information about their behaviour, or how erratic they are, or how fast they can go, or how much they weigh, how sharp their antlers are,” Haywood continues.

“It’s mainly taking selfies, sort of going close to the deer. I haven’t seen anybody feed the deer though I think that happens quite a lot,” Scoggins says.

She is right. In 2019, the park had to put a warning on its website asking people not to feed them, after it became clear that fallow deer in the park had learnt to approach humans with plastic bags, in search of food.

“They will literally go from picnic to picnic in the summer and it’s really dangerous,” Haywood says. “It’s something that we never thought that we’d have to manage and we still don’t know what the answer is.”

Deer have learnt to search plastic bags for food- an increase in litter during lockdown put them in danger

In August, Teddington resident Sue Lindenberg posted a video to Twitter, in which two fallow deer rooted through bags of rubbish left by visitors.

In July, the Royal Parks stated that the amount of rubbish left in Bushy Park in June had almost tripled on the year before; 20 tonnes of rubbish was collected in 2020 compared to seven tonnes in June 2019.

“There have been a number of deer who have died without us knowing, and then you do an autopsy and they are full of plastic because they have taken sandwiches or people have fed them,” Haywood says.

“It’s not natural behaviours for them to approach you and actually if they do you should move away. That’s a very negative side of what’s happened and we don’t want that to carry on. It’s really awful.”

It is not just litter and petting that can cause the deer distress. Haywood believes there has been an increase in dog ownership in recent years, meaning a rise in dogs let loose in the park.

“Another one of the reasons why the ranger service happened is because there are so many more dogs in the park and not all dog owners are as sensible in here as they should be,” Haywood says.

We have all seen the Fenton video, but the reality of dogs chasing deer is not quite as humorous as the viral sensation suggests. Last month, a man was charged under park regulations after a dog attacked and killed a deer in Richmond Park. It is the fourth time a deer has been killed by a dog, since March.

“The deer actually get really quite upset by them, there are injuries and stuff, so we’re not just being mean by saying ‘put your dog on a lead, there’s a deer herd up there’ – it’s all for your dog’s safety, and your own safety,” says Haywood. In short: keep your dogs away from the deer.

Rangers will be back after England’s second lockdown ends

The Bushy Park volunteer rangers are not on hand to advise and interact with visitors through England’s second lockdown. The role is purely public-facing, and so it is safer to put the ranger role on hold. But come December, Scoggins will be back, wrapped up in hat, scarf and orange jacket, raring to go.

Life in the park has had its challenges, considering the excel in popularity. But the overwhelming feeling of those who use it, and those who protect it, is one of gratitude.

“It’s the best job I’ve ever done. Just talking to people – it kind of renews your faith,” Scoggins says.

“The majority of people here are just trying to enjoy life, enjoy nature, do their best to look after the environment, and it’s so rewarding. I would do it seven days a week if they let me.”

It is no wonder why. Beyond the trees and the deer, there are stag beetles and skylarks, waterfowl and water voles. It is a green oasis on our doorstep, and the park rangers want to ensure it is here for generations to come.

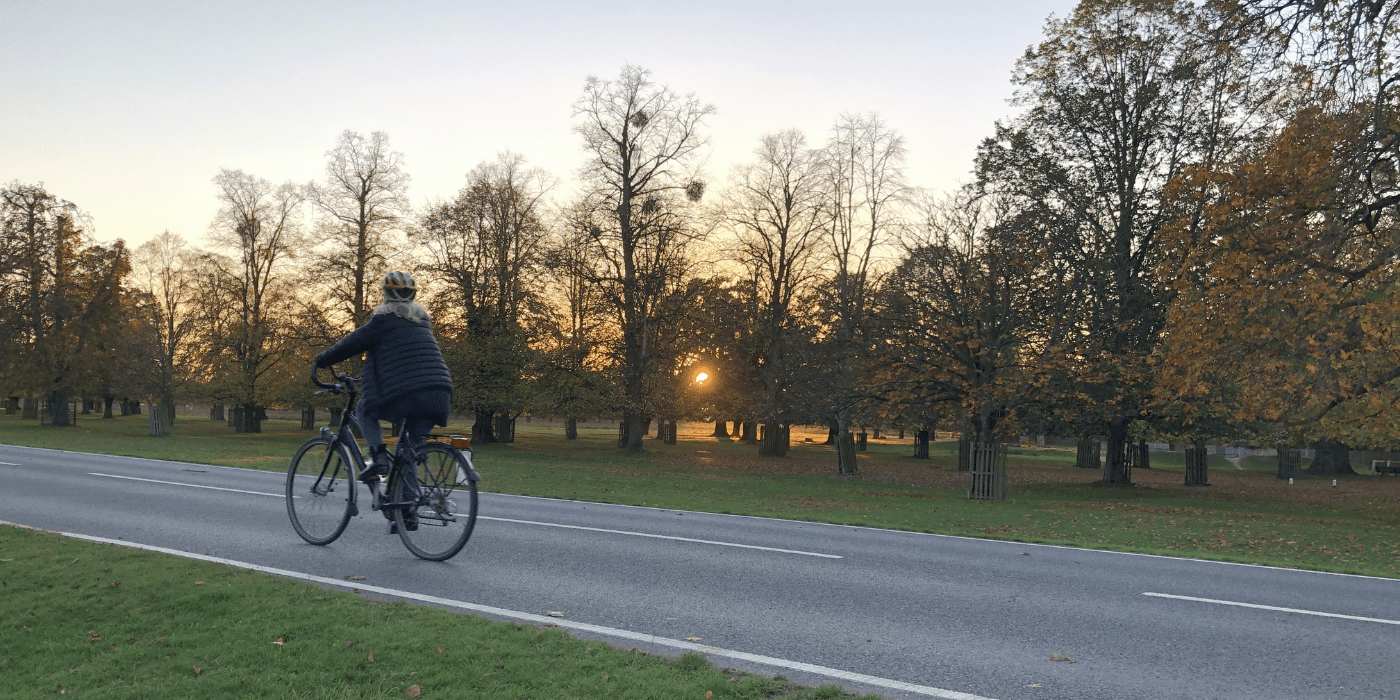

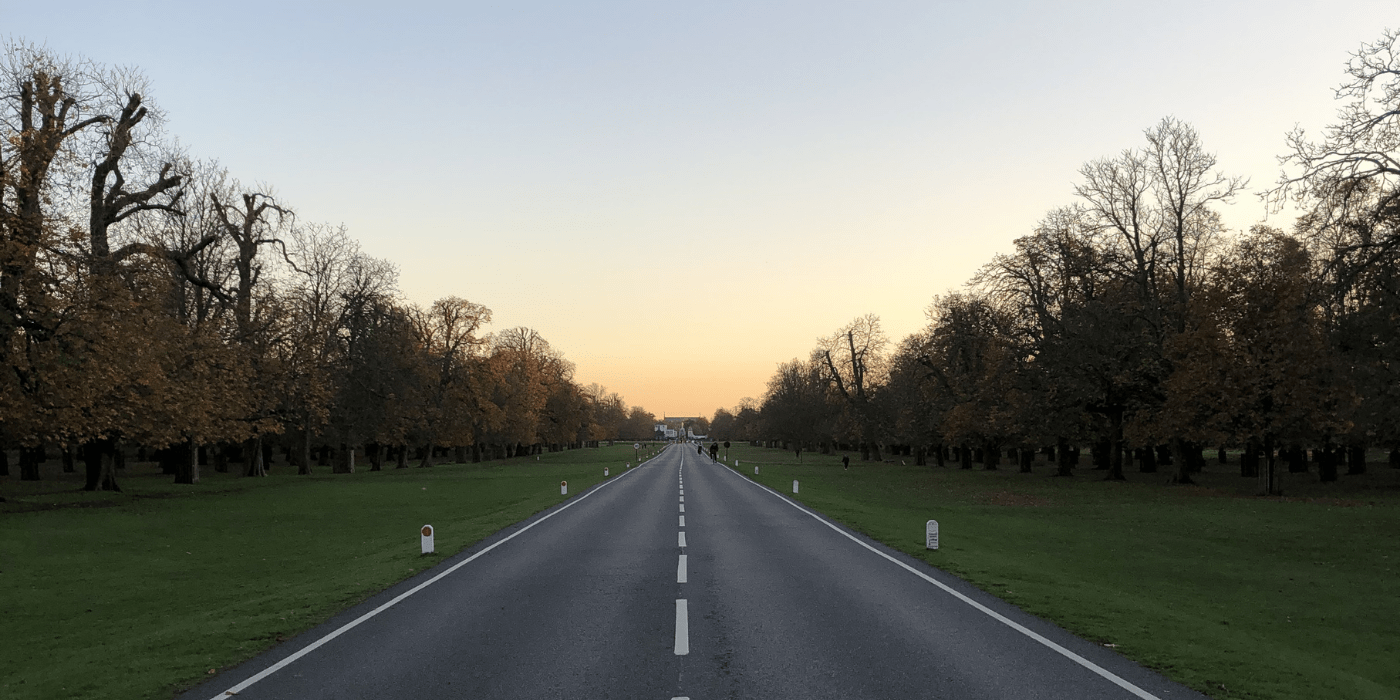

As Scoggins and I make our way through the park and cross the famous Chestnut Avenue, which unravels from Hampton Court Palace down to Teddington Gate, the sun is melting into the horizon, illuminating the park’s very best features; the sky a pale blue and cloudless.

A kestrel flies overhead. A woodpecker drills in the distance. The park is ours to relish, and ours to look after. There is no better time to do so.