The borough’s historic link to a unique British custom celebrated on Shrove Tuesday.

Nowadays, Shrove Tuesday is associated with eating pancakes. But for centuries, Kingston upon Thames had strong links with a very different tradition.

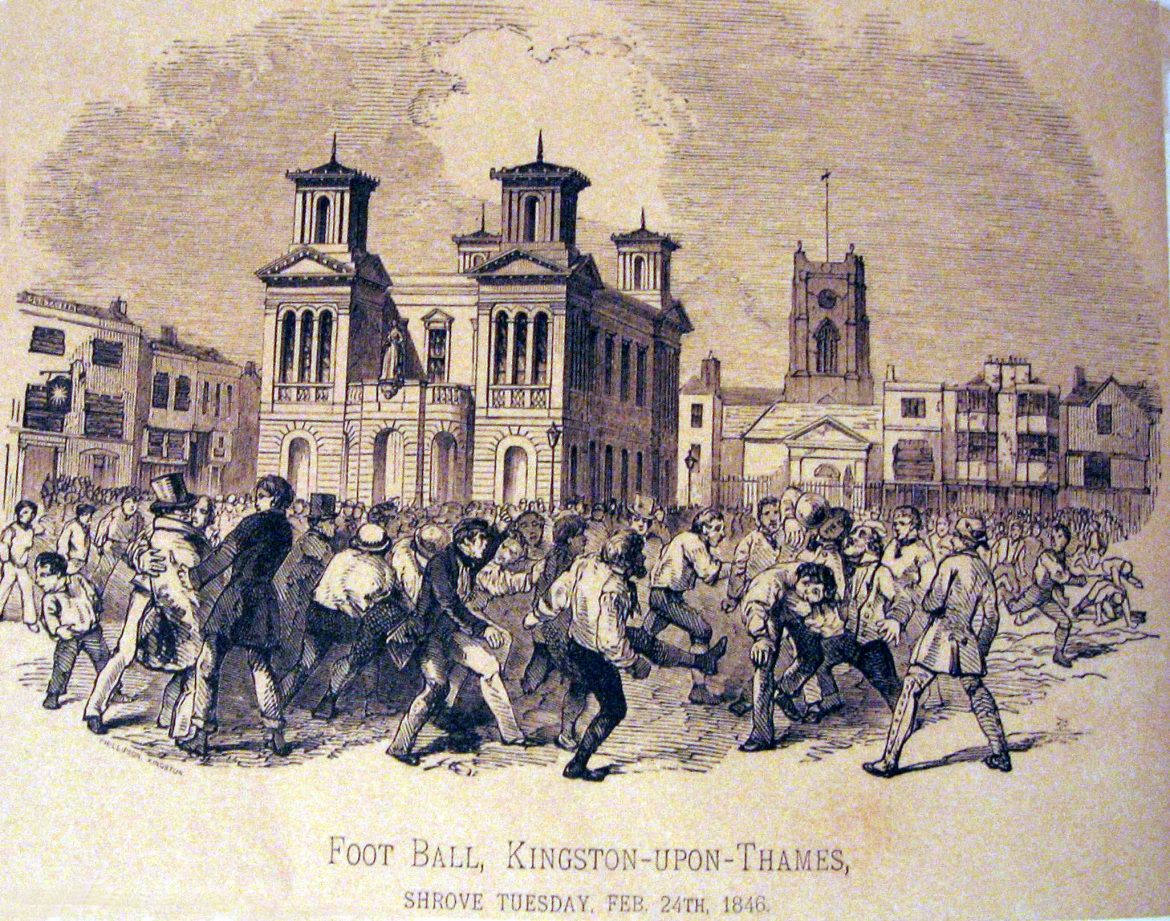

On Shrove Tuesday, hundreds of men and women would gather in Kingston’s Market Square, awaiting the sound of the Pancake Bell.

The bell signified that a riotous game of Shrovetide Football was about to ensue.

Julian McCarthy, a local tour guide who has written a book about Kingston’s Shrovetide game, said that this is a forgotten part of the town’s heritage.

“Kingston is a historical town, it’s an ancient town… but it has got no tradition. This is the tradition we had,” McCarthy added.

So, why has this centuries-long custom, which attracted huge crowds and was once synonymous with the town, been lost in history?

The origins of Shrovetide Football

Shrovetide Football was a medieval game played annually in towns all over the country to mark the start of Lent.

The tournaments were village-wide celebrations and signified that you were entering the Lent period free of sins.

Shrovetide was also a time when rich foods such as eggs, milk and flour were used up prior to the fasting period — which is where pancake day originates.

Although it is little-known to residents now, the Kingston game used to draw crowds in from surrounding areas, and it was known as one of the largest of its kind.

An article in the Surrey Comet from 1867 described Kingston’s links to the game.

“The game of football has been played in the streets for time out of memory. How it arose even the antiquaries cannot tell us.”

McCarthy said: “Each town that plays the game has its own origin story that there was a battle, and it was a slain king’s head that people batted around, but that can’t be the case for every town.”

The earliest references to Shrovetide football come from the 12th century, and there is still one surviving example of the game in Derbyshire.

Ashbourne’s Royal Shrovetide Football Match takes place every year and attracts thousands of people, including attendance by royalty.

The rules of the game

Contrary to what the name might suggest, this medieval version of football does not involve kicking with feet.

The whole town would be split into two teams, and would wrestle for contact with the ball.

The Surrey Comet described the game in 1866 as “powerful and reckless fellows contending in a rough and tumble game for the possession of the ball… being dragged limb from limb.”

Violence and riotous behaviour were all central to the game, and it was often seen as a time where frustrations could be aired, and men could hash out their grievances physically.

There were often injuries, and even deaths, reported in the days following the game.

Despite this, McCarthy said it is difficult to understand exactly how a team managed to win the game.

“Nobody seems to have ever stated what the rules are,” he said. “Whilst the games were played elsewhere, there were local and changeable rules each year.”

It is often thought that the Clattern and Kingston bridges were the two goals, but unlike football today, scoring was not the only mark of victory.

“Touching the ball, or having held the ball, was more of a prestige than winning the game,” McCarthy said.

In Kingston, there were often three balls used at once, one of which was covered in gold.

“The gold gilding got rubbed off, and people were then proud to show they had some of the gold on them, as it showed they had been in possession of the ball.”

So, why was it banned in Kingston?

The unruly game was banned in Kingston in the late 1860s.

One reason for this was that disgruntled business owners were frustrated that they had to shut up shop during the festivities.

McCarthy said: “They put up hurdles and shutters on the windows. The shops were stopped from trading, and the traders started saying that they didn’t want it anymore.

“The gentry wanted to play the game, the commoners wanted to play the game, but the merchants and the shopkeepers started lobbying people at the council.”

The association with mob violence was also deemed no longer a good fit for an expanding Kingston.

The council’s decision to ban Shrovetide football, however, was not taken lightly by locals.

On 9 March 1867, the Surrey Comet reported the abuse experienced by Mr. Wenman, a councillor who had expressed support for banning the game. It reads:

“The crowd of nearly 200 gathered round his house, and after a deal of hissing and groaning, several stones were thrown, one of which broke a window and two bottles standing on a shelf.”

Additionally, during this time, there was a movement towards creating a more civilised, regulated football game.

The Football Association (FA) was formed in 1863 to correct the fact that there were no accepted set of rules for football.

The reason half-time was standard practice was so that football teams could play by their own set of rules for one half, and their opponent’s rules for the other.

The FA wanted to establish an organised game, and establish a code so that teams could play against each other by the same set of regulations.

Surbiton F.C. was one of the eleven suburban London clubs present at the FA’s first meeting, suggesting there was local support for a much more civilised and regulated sporting tradition.

Kingston’s link to Shrovetide was then lost, but local historians like McCarthy hope to keep the game in play.

“It got banned, and it’s not going to come back. But I just want us to have some form of tradition,” he said.

Copies of McCarthy’s book What a Lot of Collops! are available at the Kingston History Centre in Guildhall. McCarthy regularly gives tours with Kingston Tour Guides, which run every Sunday.