If you have sex standing up, you won’t get pregnant. If you have sex without a condom, you will definitely get an STI. When a school nurse looks at you, she can tell if you’re a virgin.

These are just a few of the many rumours that have been passed through classrooms and echoed through corridors of schools for decades. But where do these rumours come from?

The simple answer is children who aren’t educated about sex. The more complicated answer is that they can also come from a place of fear, shame, or confusion.

Cue the infamously embarrassing sex education lessons, now known as RSE (Relationship and Sex Education), which everyone has suffered at some stage in their school life. As daunting as they are, we all expect to come out of them less fearful, less ashamed, and less confused about sex and relationships and about the changes happening to our bodies, inside and out.

The new Statutory Government Guidance on Relationship and Sex Education was officially updated in September 2021, and this new academic year will be the first in which schools incorporate it into their curriculum. But why did it need to change?

Too Little, Too Late

Qualified sexologist from The Sex Consultant, Ness Cooper trained in youth sex education 10 years ago. She recently updated her training after the release of the new government guidance. “I originally trained in youth sex education 10 years ago, and there were so many things we couldn’t talk about and it was still very focused on STIs,” she said.

Most people remembered their sex education lessons in a similar way. The basic stuff about puberty and menstruation towards the end of primary school, around age 10/11, followed by an ever so slightly more detailed recap in early secondary school.

The new guidance will make RSE compulsory in all secondary schools, although the discussion of sex education, including menstruation, remains optional in primary schools. According to the NHS website, most girls start their period at around 12 but they can start as early as 8 years old. Similarly, boys can start puberty as early as 9.

Francesca Lagerberg, 57, attended High Arcal School in Dudley and prior to that a Catholic primary school in Sedgley. She said her first experience of RSE in primary school was “laughably short on detail”.

Lagerberg said: “It was a Catholic school so the whole idea of sex was a bit out of the wheelhouse of the priest and teachers.” She recalled the girls being taken aside around the age of 10 to talk about periods so they didn’t panic about them.

“Secondary school did have some lessons, but it seemed to mainly involve the reproductive habits of frogs and flowers. Little of these lessons seemed to bear much resemblance to human life,” she said.

“Biology lessons covered our anatomy and basic reproduction in a no-nonsense, factual way making everything sound very dull, which seemed a deliberate policy.”

Alan Gravett, 57, went to St Joseph’s College, an all-boys Catholic school in Upper Norwood, and said that their teacher “seemed embarrassed to teach the lesson, and the content was overly technical”.

Lack of Inclusivity

You might be thinking to yourself: but this was decades ago, surely things have changed since then? But experiences in the 21st century didn’t get much better.

Jessica Defer, 31 (then age 14) was being taught sex education at Coombe Girls Secondary school, New Malden in the early 2000s. “Put a condom on this wooden penis. Carry around this bag of flour for a week and pretend it’s a baby,” she was told. Even after the new framework for Personal, Social and Health Education (PSHE) was published in 1999, the curriculum remained relatively unchanged.

“At this point Section 28 was still in place which made it illegal to give any education on same sex relationships because it came under promoting homosexuality to children,” said Defer. “As a direct result of this I grew up as a gay teenager with massive amounts of shame, terrible mental health and not practicing safe sex because there were no resources whatsoever.”

The new curriculum recognises that young people may be discovering or understanding their sexual orientation or gender identity. It provides equal opportunity to explore the features of stable and healthy same-sex relationships, which should be “integrated appropriately into the RSE programme, rather than addressed separately or in only one lesson”.

Separating students?

Fast-forward another decade, and sex education still seemed to be failing its students. “It was all very scientific. It didn’t tell you any of the practical things that you need to know when you’re sexually active,” said Gabrielle Ferlita, 22, who attended Woking Highschool, Surrey.

People of all ages and genders interviewed for this story said that what the curriculum needed was to put the theory of sex and relationships and the actual practice of them together to give people a proper, real-life-based sex education. But there was one thing that did seem to draw a divide in opinion: separating boys and girls for sex education lessons.

“Boys and girls were split in all sessions. I think this is the right choice as it allows people to feel more comfortable and express their views. If it were mixed groups, I feel that some people would not want to discuss anything, because they may be embarrassed,” said Arun Holloway, 21, who went to Heathside School, Weybridge.

Of the men interviewed, 75 per-cent revealed that they preferred (or would have preferred) their sex education classes to be separate from female students, mostly due to embarrassment. In contrast, all the women said that they would prefer integrated sex education classes.

Ferlita said: “I can see why they separated us because we would’ve felt even more embarrassed, but I think a lot of that embarrassment comes from having to hide it. Why should we have to hide having a period? It’s a normal healthy thing that a woman has to go through…

“A lot of those boys are going to become partners to women, or they’re going to become fathers to girls, so it’s not like it doesn’t affect their lives at all.”

Anna Rigby, 21, who attended Bishop Rawstorne Academy, Lancashire, said: “We grow up to think pregnancy and contraception is only a female issue, and that condoms as form of protection are something only boys should think about, when we should all be thinking about everything in mutual sexual relationships.”

According to the Office of National Statistics in 2018, 94.6 per cent of the UK population aged 16 and over identified as heterosexual, indicating that most students will end up in male/female relationships. Surely then, it is beneficial for boys and girls to learn about relationships and sex together in a safe environment where they can ask questions and come to better understand each other?

Knowing the Signs of Abuse

Whilst the new guidance does not specify whether boys and girls should be taught together or separately, it does say that RSE should enable them to know what a healthy relationship looks like and teach them about what is acceptable and unacceptable behaviour in relationships

Moreover, it details that grooming, sexual exploitation and domestic abuse, including coercive and controlling behaviour, should also be addressed sensitively and clearly, which will give students the ability to spot warnings signs of these behaviours much sooner.

Several women also mentioned the need to cover topics such as consent and sexual harassment and assault. Research from a review of sexual abuse in schools and colleges conducted by the UK Government indicated that approximately one-quarter of cases of all child sexual abuse involved a perpetrator under the age of 18.

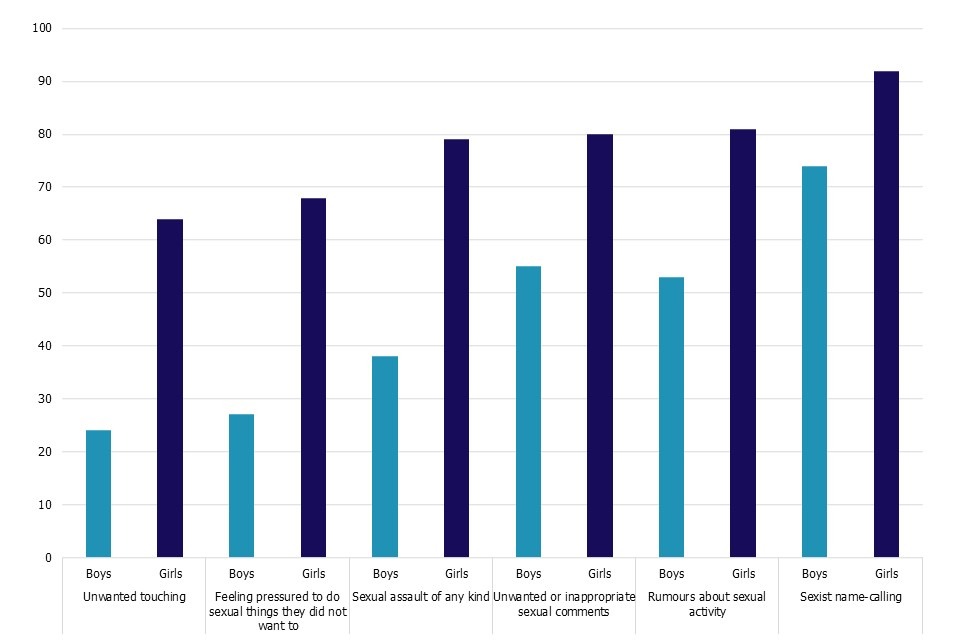

The review also revealed that “Boys were much less likely to think these things happened, particularly contact forms of harmful sexual behaviour, as shown in the chart below”:

Sourced from government review of sexual abuse in schools and colleges.

The government-run review also included many forms of sexual abuse in its questionnaire, from non-contact forms which can happen face-to-face or online, to the more obvious contact forms of abuse. It showed that, in one school, “girls understood that sexual harassment was ‘a big deal’ but boys did not recognise that it was happening or identify it as abuse. Girls in this school described routine name-calling, sexual comments, and objectification. Boys described jokes and compliments.”

A Safe Space to Learn

“I think everyone should anonymously be allowed to ask questions in a judgement free space, perhaps someone they can email or somewhere they can anonymously leave a question,” said Izzy Schulte, 21, who studied at Heathside School, Weybridge.

Cooper said that, with the help of the new training and guidance, “an educator should be confident enough to give a good answer to the questions they [students] have”.

The guidance reads that RSE lessons should be delivered in “a non-judgemental, factual way and allow scope for young people to ask questions in a safe environment.”

Cooper said: “We have come a long way in these things. We are avoiding less, as even 10 years ago we used to sweep things under the carpet. We are now more ready and trained to answer the things we need to.”

The Royal Borough of Kingston upon Thames commented on the new curriculum, saying: “Children are more likely to know what abuse is, both in person and online, and how to seek help if they need it. As they grow older, young people with good age appropriate RSE teaching are more likely to experience consensual, respectful intimate relationships and look after their sexual health into adulthood.”

While the odd ridiculous rumour might still manage to whisper its way through schools, with this new RSE curriculum the shame, fear, and confusion that has led many students and adults to suffer in silence is finally being tackled. School is a place where children and young adults should feel safe and able to learn without judgement and the new Statutory Government Guidance is a huge step in the right direction. Though, a word of advice to those in charge: let’s not wait another 20 years before it’s updated again.