Listen to the review here.

Brimming with contemporary resonance from Russia’s war, refugee camps, and even the cost-of-living crisis, the Rose Theatre’s Caucasian Chalk Circle, adapted by Steve Waters, is a captivating morality play.

In the first major London production in 25-years, director Christopher Haydon, has approached the play with exuberant energy.

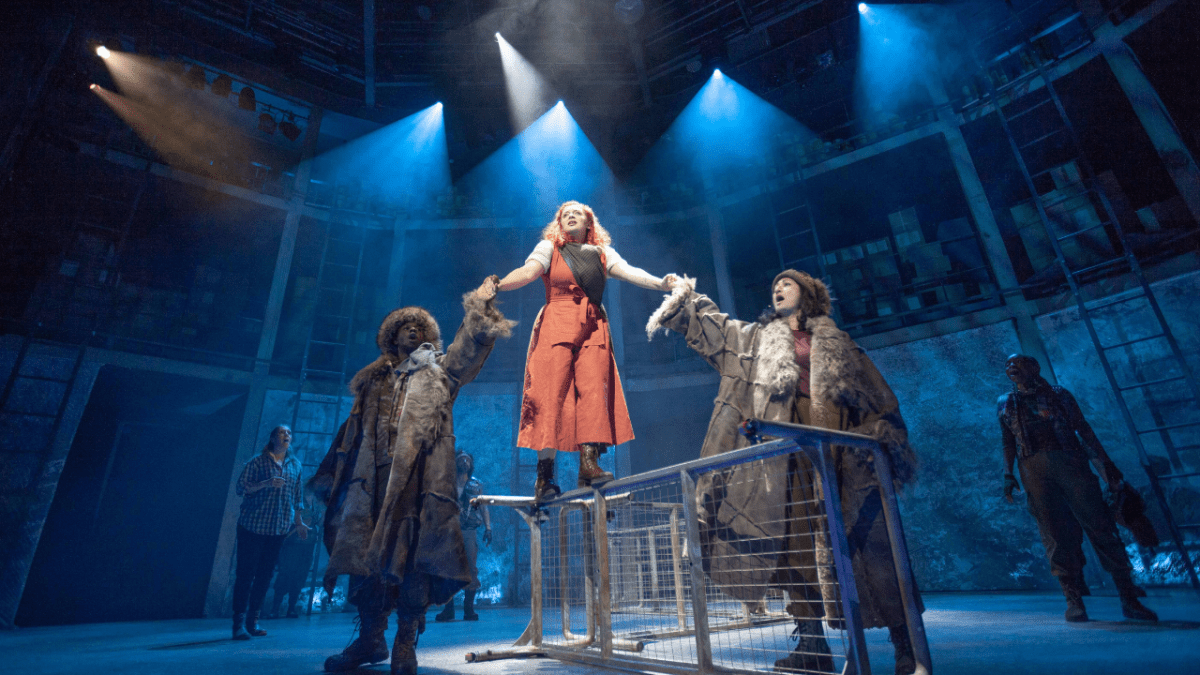

After her fandango with the Cinderella Musical and Andrew Lloyd Webber, ‘Grusha’ is Carrie Hope Fletcher‘s first try at a ‘straight’ play in recent years.

If you’re just going to hear her crystalline singing, you may feel Fletcher is under used. Rather, her clear voice pierces through the clamour of the plot and caricatures, bringing a neat focus back to the play.

The grungy-folk narrator keeps the plot turning with musical interventions. With a beautifully broad Yorkshire accent, Zoe West is perfectly suited for this role of a cheeky third-person narrator who joins in on the action.

Starring as the ‘Judge’, Jonathan Slinger’s performance is exceptionally ruthless in comedy and scatological wit.

He holds the stage and adds some characteristic ‘umph’ just as the story seems to lag.

The Judge subplot detracts from the previous Grusha-storyline, but the contrast between the Judge’s rogue justice ethics in a kangaroo court which highlights Grusha’s compassion as the true hope for humanity.

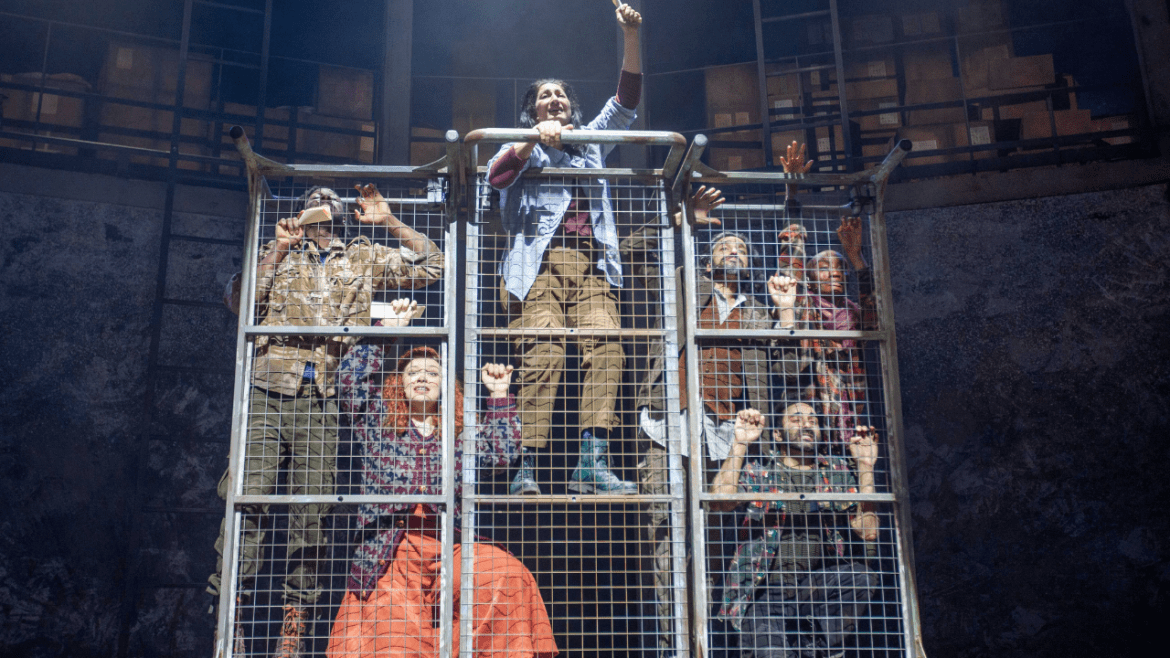

The play starts in a somewhat disappointingly stereotypical set of a refugee camp. The characters clamber over each other, in front of a detached United Nations official, squabbling about when they will find a home.

As a ‘distraction’ from their plight, a storyteller-cum-folksinger (Zoe) introduces a play where everyone takes part. And the fun begins.

Brecht’s traditional style of Epic theatre is celebrated throughout. Grotesque comedy and slapstick abounds. There was even a cream pie thrown at one point.

Surrealism, episodic structure, role play, direct address, absurdity and classic Epic conventions create the distance between the audience and the action on stage.

Contemporary issues of power, ownership and displacement are stretched and strained in an unfamiliar and farcical context. Rather than empathising with the difficulties Grusha endures, the audience critique the societal structures which inflict them.

A triumph in storytelling, this play-within-a-play format reveals layers of nuance.

Some lines were on the nose, references to the Governor’s ‘special operation’ and ‘strategic withdrawal’ left no confusion as to which Russian invasion was being alluded to.

Farcical it may be, but there are some heavy criticisms of the worst faces of humanity.

Thematically speaking, Brecht loved his morals. All the main targets get their criticism: the monarchy, the bourgeoisie, the law, the army, and religion.

Some viewers may be disheartened by the classic proletariat characters played with predictable northern accents. However, the Epic genre is founded on easily identifiable stock characters, adding to the farce.

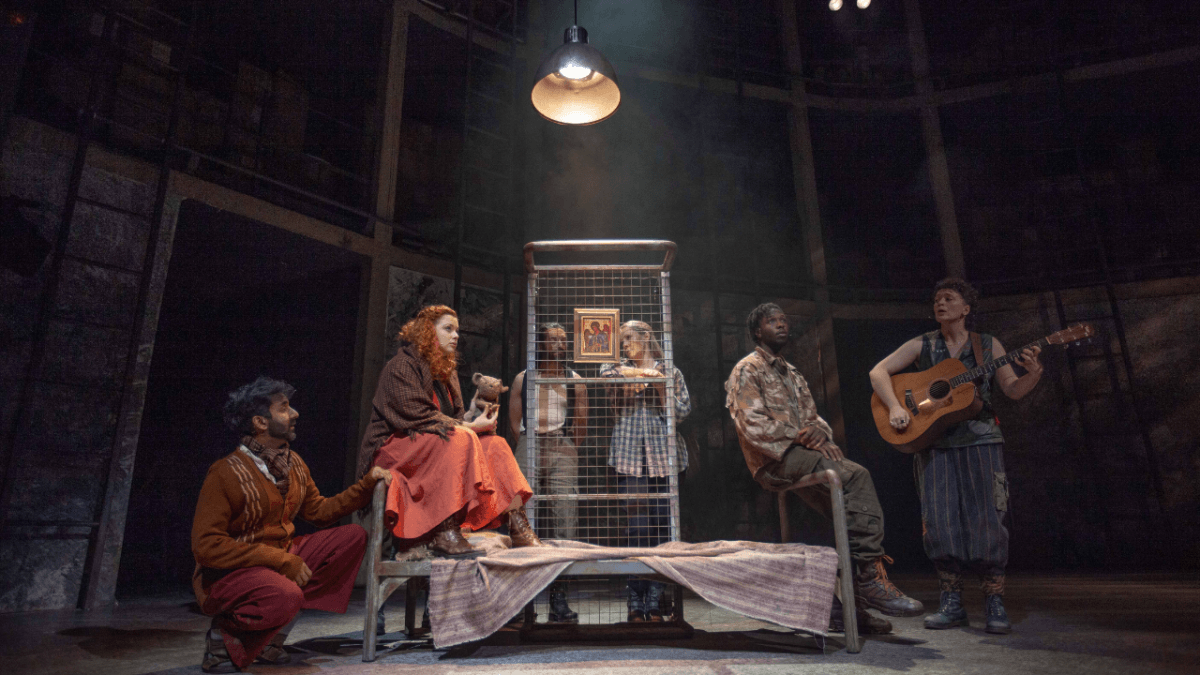

The 1944 authentic script is interwoven with music and song; Brecht did not publish an official score, but left it up to the producer’s discretion.

Michael Henry’s original music with a dark and jagged score makes it exceptionally unique. Borrowing from different cultures and different chronologies, the never-ceasing harmonies reinforce the sense of displacement.

Even if you’re not a typical musical fan, the deeply rhythmic score will be running through your head. This performance doesn’t wash over you but leaves a resonance for days.

The story is a bit lopsided: the first half is a long-haul flight of 90 minutes (same time from London to Hamburg). Momentum is lost slightly as the Judge (Jonathan Slinger) and his backstory dominate the second half.

The ‘play’ is set in an ambiguous country of Caucacus, somewhat near the Russian borders and Persia. The capital is quickly submerged in the throes of civil war. The high-strung Governor’s wife (Joanna Kirkland) escapes, forgetting her baby son in the panic over which dress she should bring.

Grusha (Carrie Hope Fletcher), a maid in the palace, adopts the baby as her own and embarks on a long and perilous journey to find refuge for the child. Denied hospitality or help from those around her, Grusha does all she can to keep the child safe, even sacrificing her own happiness.

She is reprimanded for stealing the Governor’s child and claiming it as her own.

The case is tried by a vigilante Judge, the only left alive by the regime. He devises a test to see who the real mother of the child is: the chalk circle.

You don’t have to be an avid theatre goer to watch this play. Its caricatured playfulness makes it laugh-out-loud funny.

If you’re interested in your classics, it’s a fascinating contemporary spin on a Brechtian masterpiece. Although the number of F-bombs give an appearance of irreverence to the original script, the Brechtian spirit is true to form.

Even if you’re a theatre novice and have never even heard of Brecht (school days of drama are a distant memory, right?), this play injects mischievous surrealism into serious, universal topics of ownership, displacement and ultimately justice.

At the Rose Theatre, until October 22. Further information and ticket bookings can be found here. Students get £5 off, where it applies.