Nu (B.1.1.529), now known as Omicron, is the latest variant of Covid-19 to be discovered. After living with Covid-19 for almost two years, people are expecting turbulence to follow this announcement, but it might not be as bad as it seems.

Here are a few of your questions answered.

Where did Omicron come from?

The new variant was first detected on Tuesday 23 November by scientists in South Africa, although it’s important to note that this does not mean it originated there. It simply means that South Africa was the first to alert the World Health Organisation to the variant’s existence.

Professor of Genetics Tim Spector, who runs the ZOE Covid study, said: “Actually, South Africa has less cases per million than we do in the UK and most people believe the virus has been around for up to four weeks.”

It is easy to jump to conclusions and point fingers at other countries when a new hurdle slows us down in the race against Covid-19, but the fact is, at least 24 countries across the world have now reported cases of Omicron.

Scientists are exploring the possibility that the unusual pattern of mutations may have emerged during a chronic infection of an immunocompromised person, such as an untreated HIV/Aids patient. However, the origin of the new variant is still being traced.

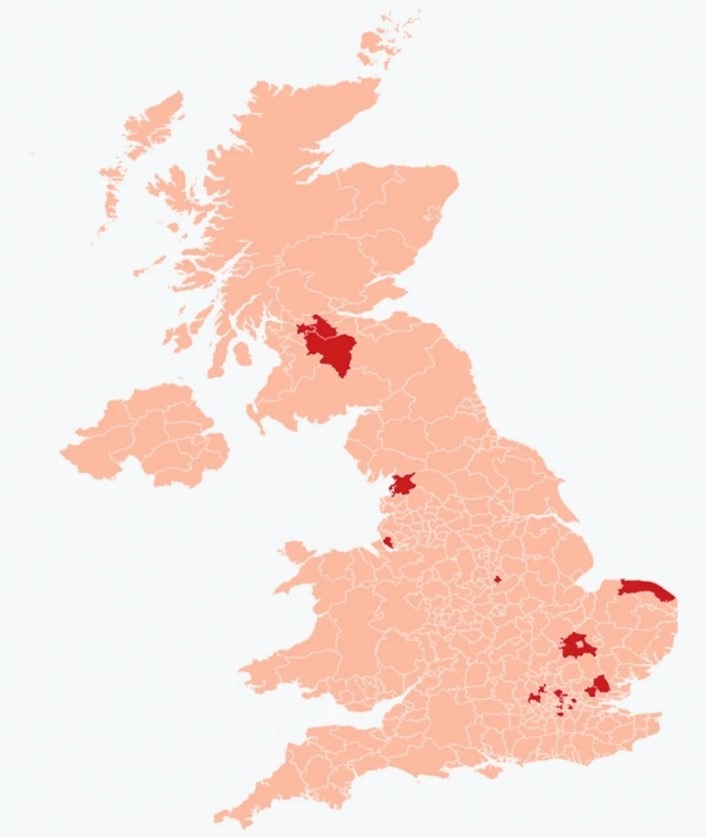

So far in the UK, 42 cases of Omicron have been confirmed, with 29 in England and 13 in Scotland.

What are people so worried about it?

The difference between Omicron and previous strains of the virus is the number of mutations on its spike protein. The spike protein is what binds coronavirus cells in the human body, so more mutations on the protein means that it is better at getting into our bodies and infecting us.

Omicron has been found to have more than 30 mutations on its spike protein, which is more than double the number carried by the Delta variant.

Virologist and professor Suresh Kuchipudi said: “While the unusually high number of mutations in the omicron variant is surprising, the emergence of yet another SARS-CoV-2 (Covid-19) variant is not unexpected.”

Kuchipudi highlighted the importance of remembering that this is not a new virus. Omicron is a new variant of the same virus that we have been dealing with for almost two years now.

This was further reinforced by Prime Minister Boris Johnson in his press conference on Tuesday. “Today our position is, and always will be, immeasurably better than it was a year ago,” said Johnson.

Though the data is minimal at this stage, there is still no indication that this variant of the virus causes more severe symptoms. It is also unclear whether it will take over from the Delta variant as the dominant strain.

What we do know is that we are better equipped as a nation to combat the possible effects of this new variant.

Will the vaccine work against Omicron?

Vaccine efficacy has been a huge concern nationwide in light of the new variant. Professor Francois Balloux, a researcher at UCL Genetics Institute, said: “There is little doubt that Omicron is good at (re-)infecting immunised hosts as it is expected to be less well recognised by neutralising antibodies, due to the large number of mutations in the S protein.”

But, according to Professor Anne von Gottberg from the National Institute for Communicable Diseases, people who have been previously infected or vaccinated are developing less severe symptoms from the new variant. This means that while our antibodies may not stop infection completely, they do have the potential to keep more severe symptoms of the virus at bay and, in turn, reduce the number of hospitalisations and deaths.

Only 36 per cent of South African adults are fully vaccinated, compared to the 80.70 per cent in the UK. Omicron has already had a much worse impact and is spreading more quickly in South Africa, whereas its effect on the UK population has, so far, been less severe.

The government reiterated its previous advice on vaccinations in Tuesday’s press conference. The prime minister said: “Every day our scientists are learning more about this new covid variant but there’s one thing that we already know for sure and that is that, right now, our best single defence against omicron is to get vaccinated and to get boosted.”

In line with advice from The Joint Committee on Vaccination and Immunisation (JCVI), boosters will now be offered to everyone over 18, and the minimum gap between the second vaccine dose and the booster has been halved from six months to three months. With this massive push for vaccinations nationwide, it is hoped that all eligible people will have been offered their booster jab by the end of January.

The possibility of a new vaccine that could better combat the Omicron variant is not completely out of the question, but could take around four to six months to be developed and manufactured. For now, the guidance is to get the currently available vaccination, as well as the booster jab when invited.

Why are other restrictions coming back?

There is no doubt that Omicron cases in the UK will continue to rise because, unlike two weeks ago, scientists are now aware of it and actively looking for it.

“What we’re doing is taking some proportionate precautionary measures while our scientists crack the omicron code,” said the prime minister on Tuesday.

He was backed by health secretary Sajid Javid, who said: “There’s a lot we don’t know of course, and our scientists are working night and day to learn more about this new variant and what it means for our response.”

“Our strategy is to buy the time we need to assess this new variant while doing everything we can to slow the spread of the virus and to strengthen our defences.”

The new targeted measures that were introduced this week are:

- All international arrivals must take a Day 2 PCR test and self-isolate until they receive a negative result.

- All contacts of suspected Omicron cases must self-isolate, regardless of their vaccination status. They will be contacted by NHS Test and Trace.

- Face coverings are now compulsory in shops and on public transport. All hospitality settings will be exempt.

The government also said it would be focusing particularly on measures in place at the borders. In addition, the prime minister stressed that, while nothing is being ruled out, the idea of a full implementation of ‘Plan B’ (a full lockdown or something of a similar nature) is unlikely.

As always, all measures will be kept under review over the coming weeks.