A mother from Worcester Park was able to save her son’s life by taking him for a preemptive heart screening just before the first lockdown began.

Niki Mason signed up her 14-year-old son Finn for the heart screening, offered by Cardiac Risk in the Young (CRY), last year.

At the screening, Finn was diagnosed with Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome, a heart condition that causes the heart to beat abnormally fast for any period of time. The condition is congenital (present at birth) but symptoms may not develop until later on in life.

Because of the pandemic, CRY has not been able to carry out any of the screening days it used to hold in schools and other venues. The implications of this are that many young people who have not got a diagnosis are at risk of a potentially life-threatening condition.

According to the Surrey-based charity, twelve young people die from an undiagnosed cardiac arrest every week.

Doctor Steven Cox, CEO of CRY, said: “Eight months on, we have had to cancel over 21,000 screening appointments and we remain uncertain as to when and how we will be able to resume our internationally acclaimed screening service.”

Mason, who is a family support officer for Momentum Children’s charity in Kingston, found out about CRY through a friend and her job. Momentum provides emotional support to families with ill or bereaved children.

Finn’s diagnosis

“It was quite a shock. He displayed no symptoms or anything,” said Mason.

One in every 300 of the young people that CRY tests, will be identified with a potentially life-threatening condition.

Although Finn was feeling fine, he was referred to a cardiologist who taught him how to do vagal manoeuvres (exercises) if he experienced any palpitations. Shortly after his appointment, Finn had two episodes but luckily knew what to do as the doctor had explained everything to him.

In July, Finn had another episode, but this time his mum had to call an ambulance.

Finn had come in from a bike ride and started feeling very unwell. Mason knew something was wrong.

“I could literally see his heart pounding, and he was turning quite grey. I dialled 999,” she said.

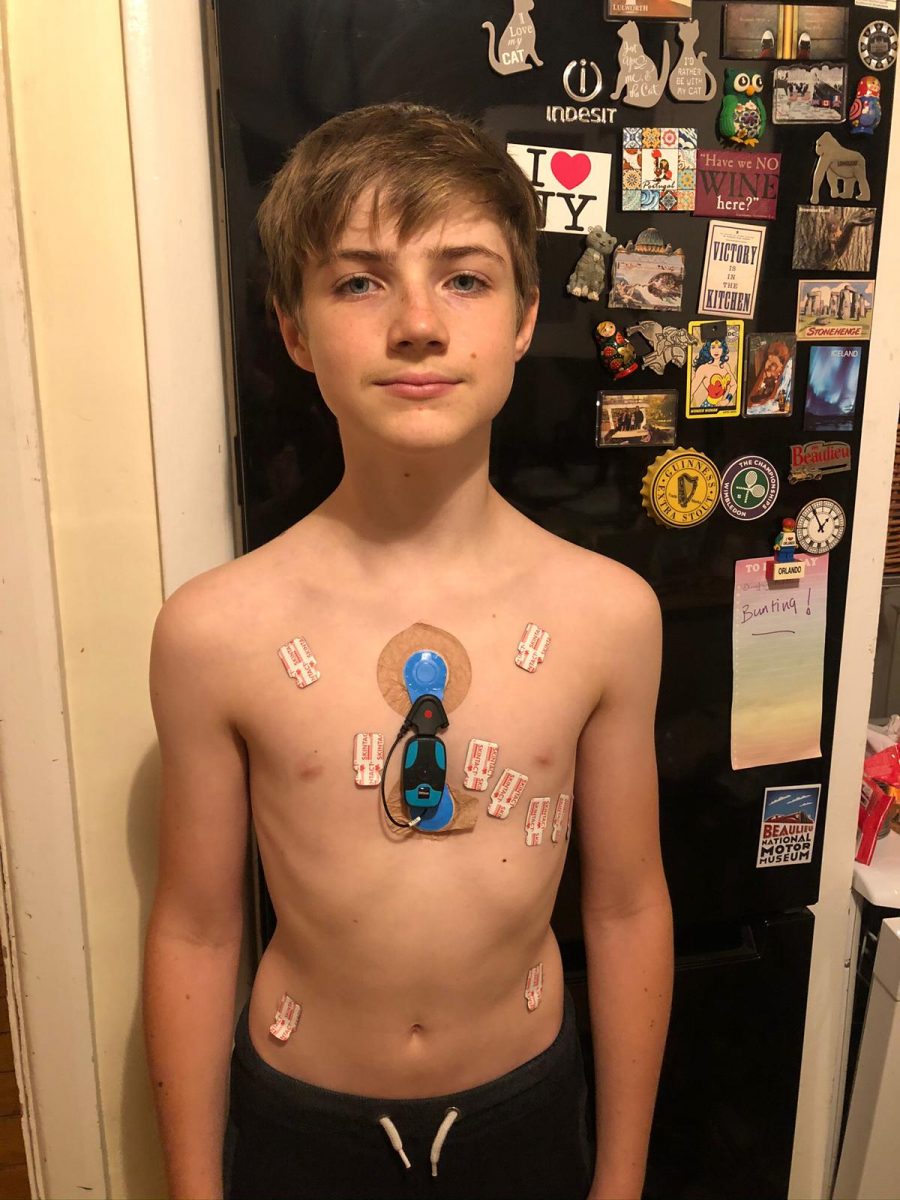

The paramedics arrived and rushed him off to Kingston Hospital. At the time, Finn was wearing a heart monitor that the doctors had sent him to monitor his heart rhythm.

The consultant said Finn’s heart rate went up to 289 beats per minute (bpm). An average resting heart rate is about 60 bpm, over 300 bpm is usually unsurvivable.

“His heart rate was so fast, anything could have happened. It doesn’t bear thinking about,” said Mason.

It also meant Finn would need to have heart surgery, but in the meantime, he could not be left alone in case he had another turn.

The day of the operation

At the end of September, Finn was admitted to the Royal Brompton Hospital to undergo a three-hour heart operation to try and fix the electrical current in his heart.

“My legs were like jelly. Finn was utterly amazing. He just took it in his stride,” Mason said.

Because of Covid restrictions, Mason could not take her husband or any other family member with her.

“I was on my own, and I just sat there staring at the clock. It was weird because when I go into the hospital as part of my job, you sit with parents who are really struggling. You see if they’re ok, hand them a tissue, chat to them, let them cry or try to divert their attention,” Mason said.

“I could have given anything to have someone ask me if I was ok. It was so horrible.”

Mason’s experience highlights the importance of charities like Momentum and CRY who support families through trauma. The rules around visiting hospitals during the pandemic have had a grave effect, not just on medical treatment, but the support and services that Momentum and CRY are able to offer.

Finn’s operation was a success, and after a couple of weeks of recovery, he was able to go to school.

Screening must resume

Last year, 14-year-old Ben O’Connell from Stoneleigh unexpectedly died, following a cardiac arrest on a school trip. CRY and Momentum have been supporting his family with their grief since the tragedy.

Ben and Finn’s stories demonstrate the need for heart screening to not only resume but to be readily available.

The screening process pioneered by CRY took place fortnightly at St George’s Hospital in Tooting, and on an ad-hoc basis at sports clubs and schools, but came to an abrupt end in March because of the pandemic.

The free screening involves taking an echocardiogram (ECG) which is fairly quick, non-invasive and pain-free.

CRY also screens Olympic athletes and works with major sporting organisations including the FA.

The charity understands why the screening has had to be paused during lockdowns but resuming screening is its main priority.

“What we desperately need is access to suitably large venues. We’ve worked really hard to ensure our screening team is appropriately prepared [in terms of PPE], with revised protocols in place [in terms of social distancing and enhanced cleaning] and are ready to get back on the road,” explained Cox.

The vast majority of CRY’s community screenings are funded by bereaved families, who have been affected by a young sudden cardiac death. The charity does not receive any government funding.

CRY believes that every young person from the age of 14 (up until the age of 35) should have access to free, expert cardiac screening. Currently, the waiting list for screening stands at 40,000.

“We are doing all we can to resume CRY’s screening programme safely, rebooking events and working through our ‘backlog’ – and to ensure that awareness of the importance of cardiac screening in young people does not diminish,” said Cox.

To be added to the waiting list for a screening, you can visit www.testmyheart.org.uk.