Even if you haven’t read or watched at least one version of William Golding’s novel, you can’t escape references of this classic in films and other literature.

But director Amy Leach has added a modern interpretation to a new production of the story about a group of schoolboys stranded on an island.

Lord of Flies had a quick run at the Rose Theatre from April 18-22. Watching on the play on its opening night, you could feel the Rose was flexing its credentials as it co-presented another highly anticipated and dynamic production.

The concept of the play focusses on how, left to their own devices without the guidance of ‘civilising’ adults, school children try to govern themselves and establish order. Bluntly, morals are disregarded as anxiety and power-grabbing rages and chaotic violence ensues.

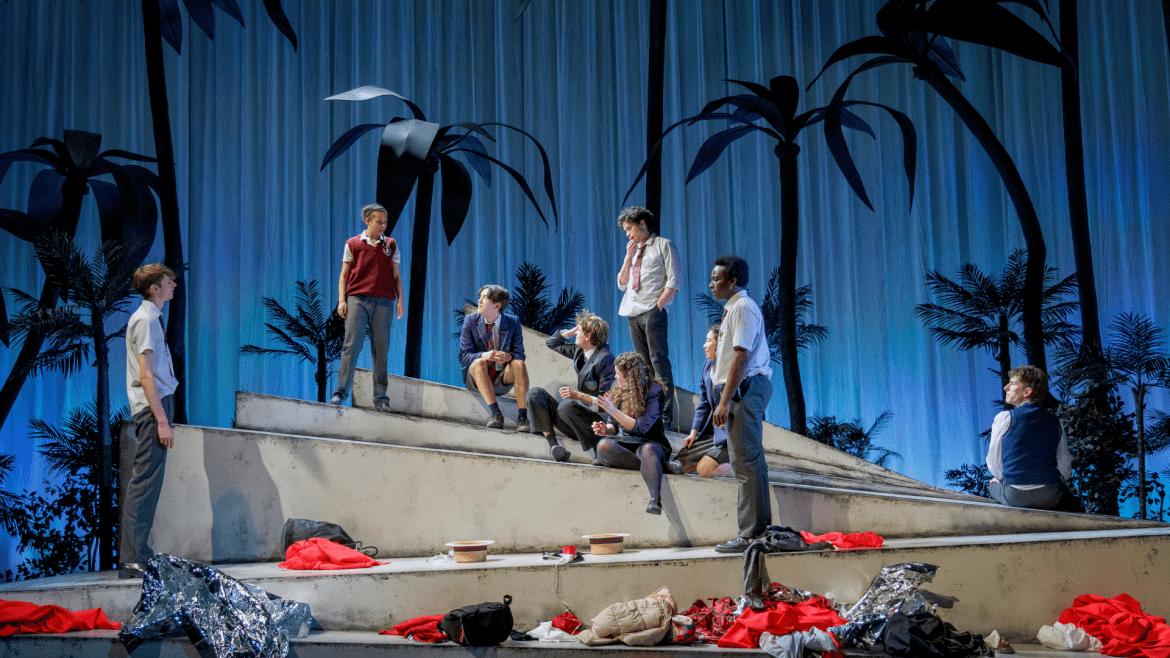

As the audience gathered to their seats, Max John’s staging was lit with a sickly yellow, illuminating the array of large forest trees. A brutalist multi-layered rock structure, indicating the cruelty of hierarchies, was both an effective backdrop and stage presence. There was an intriguing soundscape of birds and ‘jungle noises’ which was, fortunately, more like the start of a David Attenborough documentary than the title sequence for I’m a Celebrity.

Natural sounds were interrupted by a cacophony of radio news reports indicating the threat of nuclear war, a not-too-distant reality with Russia intimidating Ukraine and China flexing its muscles towards Taiwan. The nod to modernity was tasteful and not overdone with crude references.

The children line up in their school gear, somewhat reminiscent of the 14-hour lorry delays in Dover many school trips faced over Easter. The red splashed in the children’s uniform and props immediately created a foreboding sense.

Questions of “what school are you from?” thrown around at the start indicated an unavoidable nod towards privilege and the timeless contention that elite private schools carry more weight for leadership roles than lesser-known public ones.

The casting for the children was a refreshing and realistic depiction of Britain today. A commanding yet cautious Ralph was played by Angela Jones, with an already impress catalogue of work such as The Two Popes (Rose Theatre) and Jerk (BBC). Jack, the embodiment of white male anxiety and privilege, was played by utterly convincing Patrick Dineen.

Children come from different countries, regions, and abilities – the addition of two deaf students speaking British Sign Language (BSL) was an inclusive dynamic.

Scenes included signing key phrases in BSL, creating the island’s own language and adding familiarity and intimacy to the performance.

The different abilities of the students (such as Simon, played by Adam Fenton, with a seemingly nervous disposition) indicated how society is still biased towards those more physically ‘able-bodied’. Despite Simon’s physical frailty, he acts as the voice of wisdom, offering abstract existential questions of how you judge what is and isn’t good, that leave the audience pondering.

Accents abound in the geographic mix of school children, however, Northern dialect was still represented as the worn-out stereotype of the unintelligent, uncouth and lower class social outcast. Even the naval officer (representing an ironic civilised barbarity through his military involvement) was cast with a Lancaster accent. As the play was first showcased in Leeds, West Yorkshire, it would have been interesting to see how the jokes at the North’s expense landed on the Yorkshire audience.

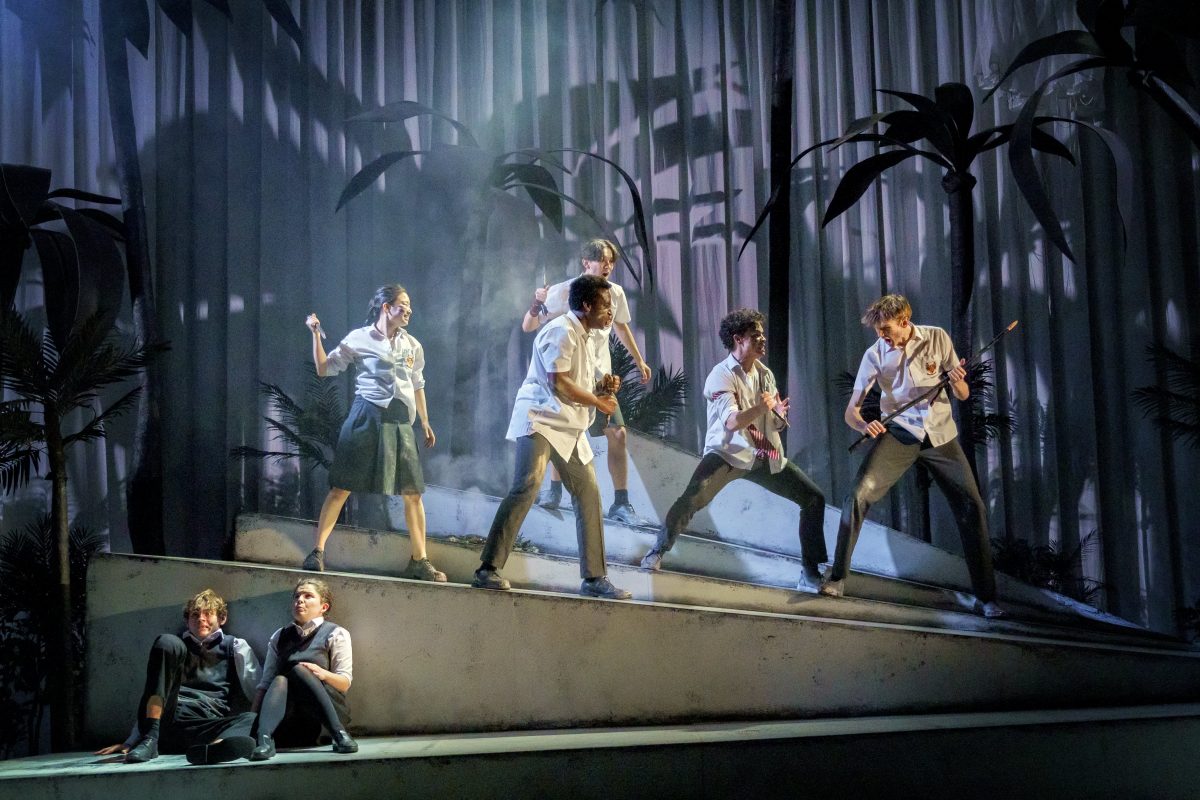

The performance itself was brilliantly Tarantino-esque, full of (fake) blood and gore. Leach’s choice to spread the blood around the cast convincingly demonstrated how easily humans get caught up in social pressure, spreading guilt yet avoiding blame.

Even the miming of violence was graphic between the children – in both the play fighting and the real attack – showing the inherent and inescapable aggression of the human condition. The red spotlight on the children and slow motion in the killing of the pig scene was more akin to a classic GCSE drama performance. Nevertheless, it controlled the pace and drew attention to human brutality.

Endings are almost impossible to perfect, and this one had a somewhat subdued sense of catharsis. Leach extends the naval officer’s confusion that the children were merely playing a game; however, this felt like the wearied “it was all a dream” cliché, almost removing the oxygen from the audience’s lungs as the two-hour long performance evaporates.

As Jack tossed down Piggy’s glasses in front of Ralph, she sobbed. The final moment of emotional release was sabotaged by such a brief dimming of the lights, as the audience try to recollect themselves, before a gleaming Ralph was already upstanding to take a bow. I felt a bit of emotional whiplash. Still, Leach offered a commanding modern interpretation of a canonical play which leaves you agasp how society continues to be inherently self-destructive. Many of the characters mimic real-life politicians and nation states as we continue to exist in a world which is unable to cope with collective responsibility. Blood, fake or otherwise, is on everyone’s hands.

Lord of the Flies is at Belgrade Theatre in Coventry from April 25-29, and the Northern Stage in Newcastle from May 3-6.