Spring is finally here. Cue longer days, lambs, sprouting bluebells and of course, hay-fever. After months of dreary darkness confounded by abysmal British weather, the season of renewal has finally arrived.

But with global temperatures rising, the insidious spectre of climate change has reared its ugly head, threatening to disrupt the delicate timing of spring by creeping forward the date at which it starts.

Dr Judith Garford, Citizen Science Officer at the Woodland Trust, warned that owing to warmer average temperatures, spring is “arriving earlier” and “becoming the new norm”.

“Our data provides the clearest evidence of a changing climate affecting wildlife,” she added.

Research by the Woodland Trust has found that leafing on trees such as larch and oak have come two weeks before the average with brimstone butterflies also spotted two weeks ahead of schedule.

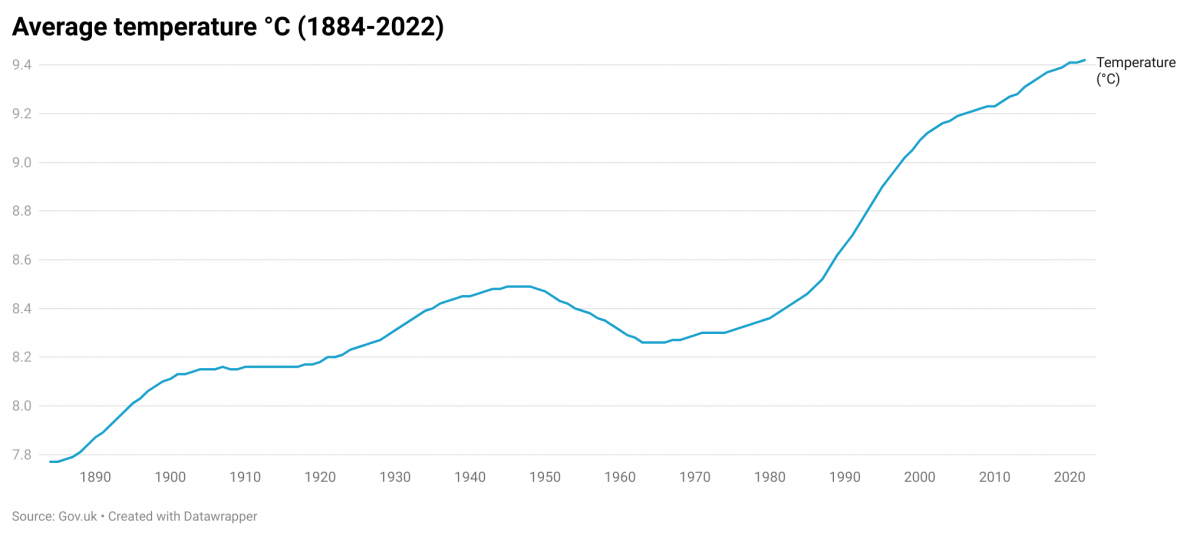

In the UK, the most recent decade has seen temperatures that are 1.0°C warmer than the 1961 to 1990 average. More ominously, all ten of the UK’s warmest years have occurred since 2003.

This February was the warmest on record, a whole 2.2 °C above average.

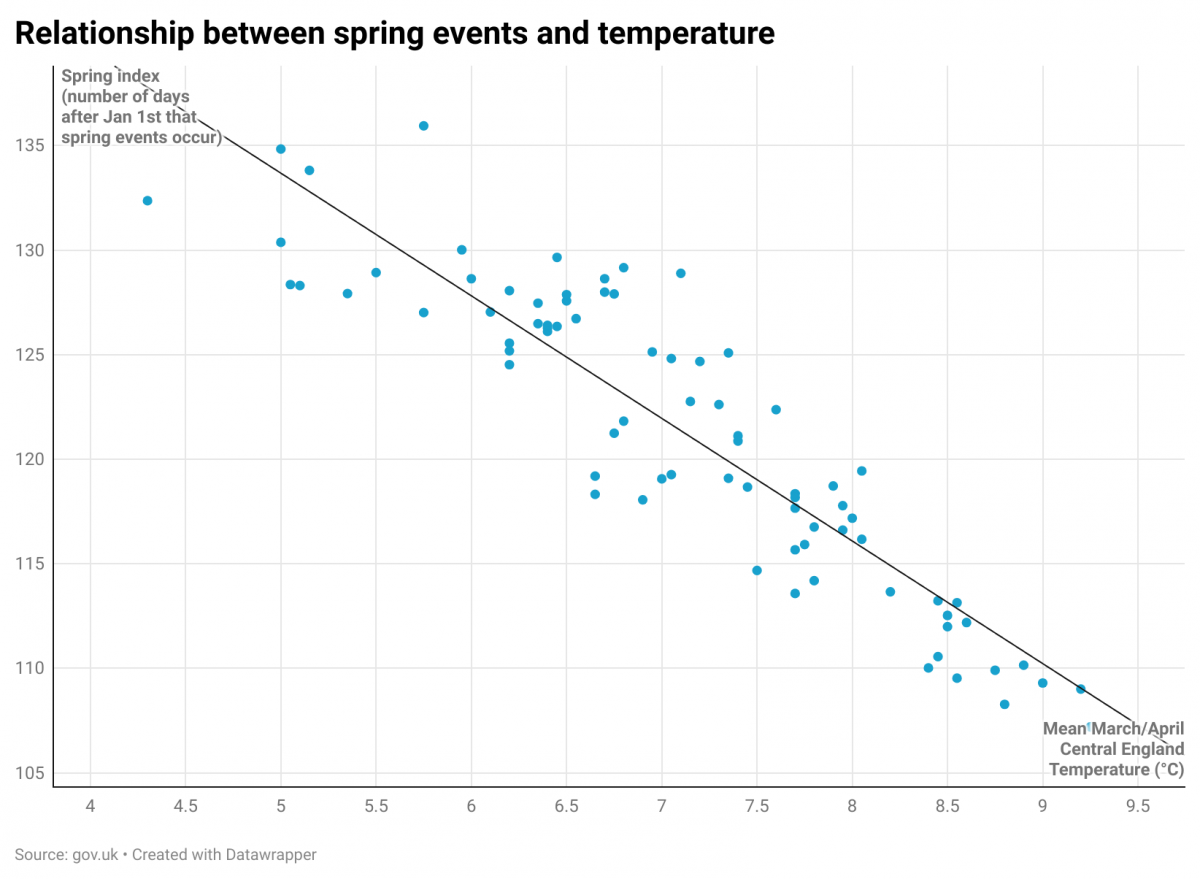

But how much of an effect do temperatures have on the arrival of spring?

According to the UK Spring Index, which measures how many days after the start of the year that spring events such as the first flowering of hawthorn or the first sighting of a swallow occur, there is a direct link between rising temperatures and the early onset of spring.

Why are early springs a problem?

Though earlier springs might be a welcome relief to those of us inclined to strip down and soak up those sunny, bone-warming rays, for many animals and plants it represents a real crisis.

This increase in temperature has had a direct effect on the onset of spring the ability of ecosystems to adapt.

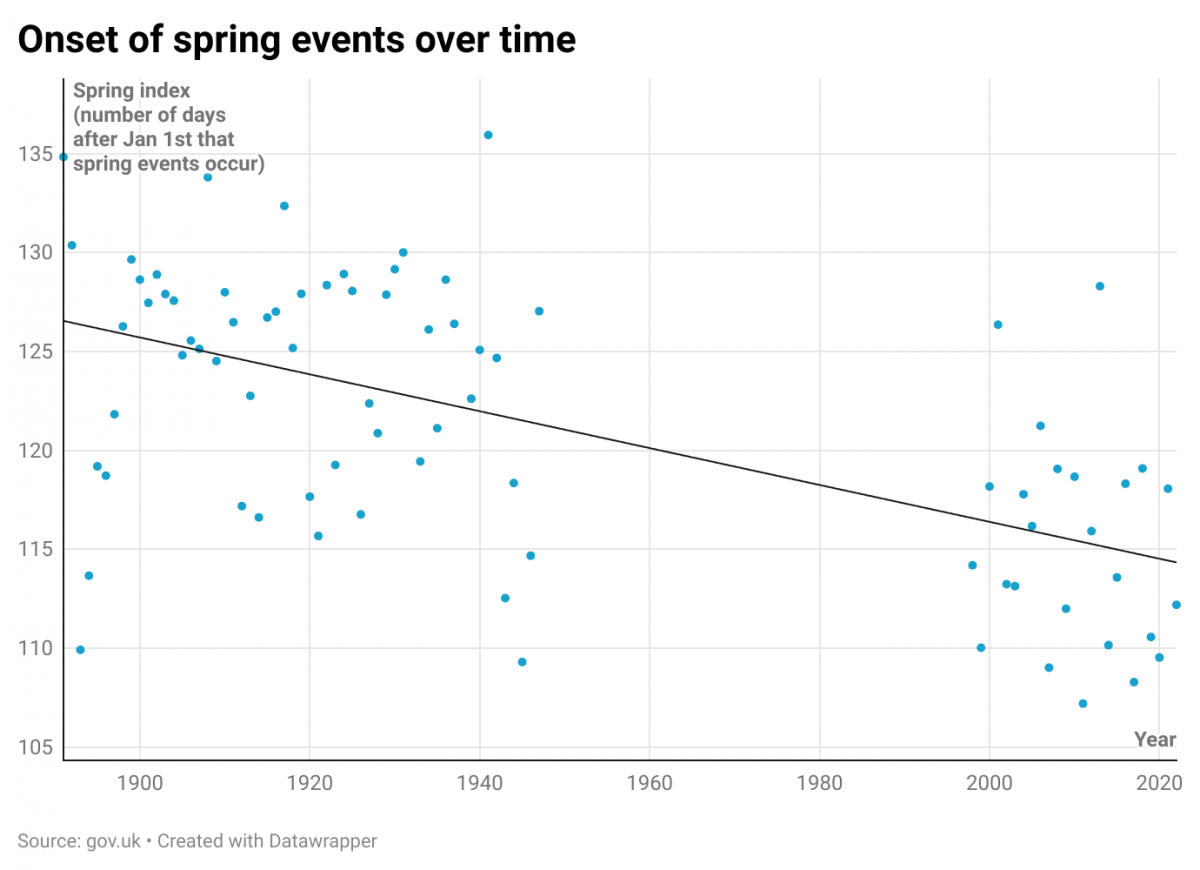

And spring is only coming earlier.

According to government data, spring events are happening about ten days earlier now than in 1891.

Tiger Beck, an environmental and sustainability consultant, explained that this is because many organisms, especially flowering plants, rely on temperature to dictate when they go through certain cycles.

Because of higher temperatures earlier on the year, many are “essentially tricked” into thinking spring has arrived, he said.

But what are the ramifications of this?

“Early blooming from trees could lead them to waste resources earlier on and therefore not have enough resources for the last bit of summer,” said Beck.

“This has a massive knock-on effect. If a tree is blooming early it will stop blooming earlier. You might have insects that rely on the pollen produced in a certain period suddenly missing their mating or larvae production windows. This effect continues up the food-chain,” he added.

Dr Garford echoed these concerns, saying that earlier springs can lead to ecological food chains becoming “mismatched or out of sync”.

For example, research led by Dr Malcolm Burgess, an Honorary Research Fellow at Exeter University, found that when oak trees leafed early in spring, it caused a surge in moth caterpillar numbers.

Blue tits, who feed the caterpillars to their chicks, needed to breed when caterpillars were abundant. However, blue tits weren’t as quick to adjust their breeding timing as the trees and moths were to the changing temperatures.

As a result, the chicks ended up being hungry after the peak caterpillar abundance, leading to less food and ultimately lower breeding success.

What is the solution?

Beck was keen to emphasise that rising carbon dioxide (CO2) levels were largely to blame.

“I’d defer to the climate scientists who’ve established the main reason for rising temperatures is the increased level of CO2 in our atmosphere,” he said.

According to Facts on Climate, every time CO2 concentrations increase by 10ppm (parts per million), the mean global temperature rises by 0.1°C.

Beck’s sentiments were echoed by Dr Garforth who suggested that the “best option” to help wildlife affected by early springs was to “reduce CO2 emissions” and to “plant more trees”.

“We must continue to monitor this ever-important data to keep tracking nature’s response”, she added.