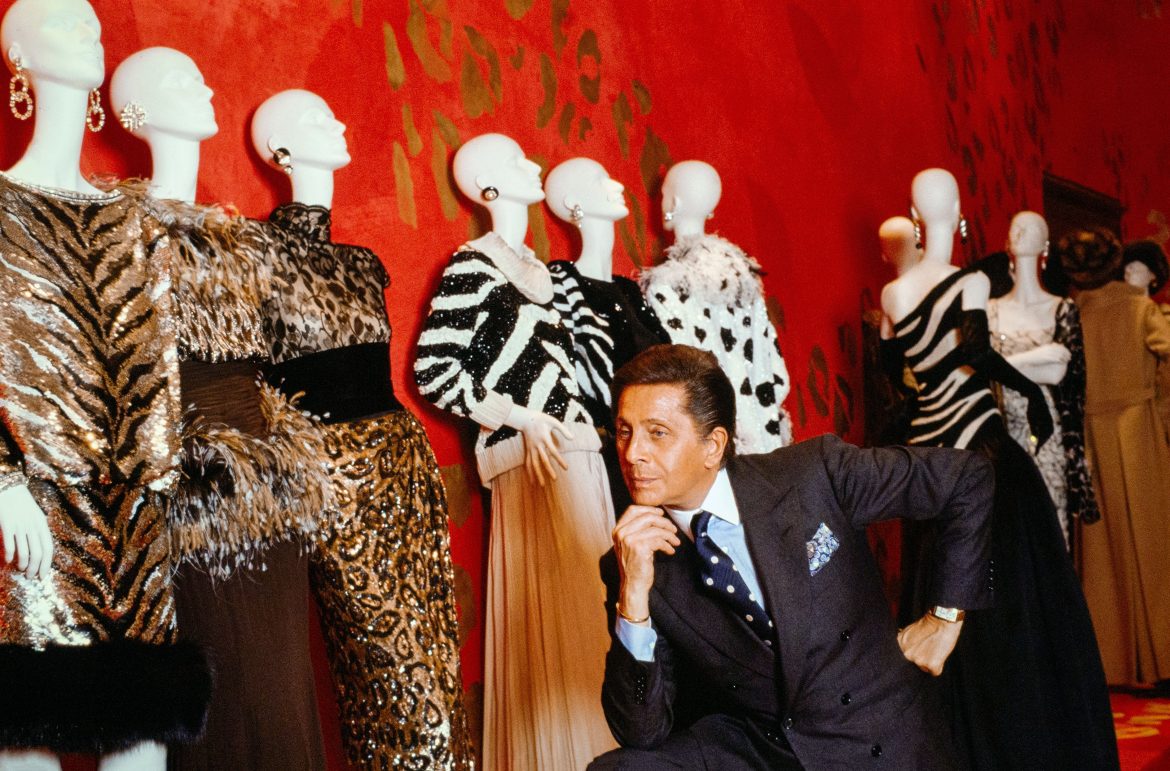

Iconic Italian designer Valentino Garavani, who died last month, leaves a huge legacy in fashion. Below, our arts correspondent considers his impact and asks where the industry goes from here

The Italian couturier Valentino Garavani, who died in January at the age of 93, was often referred to as the “last emperor of fashion”. Yet arguably he was also the last emperor of passion, for, in his absence, this title feels suddenly vacant.

Born in Voghera, Lombardy in 1932, at a time of economic recession and political shift into Fascist totalitarianism, Valentino became interested in fashion during his primary school years. Dreams of colour and beauty visited him during school hours, showing him the way out of that austere world and towards a remarkable future.

“I remember very well when I was young,” said Valentino in his biographical documentary Valentino: The Last Emperor, “I was faking to sleep and I was dreaming about movie stars and every beautiful thing in the world. […] It was the dream of my life to see those beautiful ladies of the silver screen. I remember Ziegfeld Girl, Hedy Lamarr, Lana Turner, Judy Garland. I think from that moment I decided I wanted to create clothes for ladies.”

After moving to Paris for his studies and working for big names of the time like Jean Dessès, Guy Laroche, Emilio Schuberth and Vincenzo Ferdinandi, Valentino returned to Rome in 1959, founding his own fashion house in Via dei Condotti a year later.

However, it was not until his participation in the fashion show organised by entrepreneur Giovan Battista Giorgini in 1962 that Valentino finally found his solo success. In the White Room of the Pitti Palace in Florence, Valentino’s designs paraded one after the other before an international public. His creations were refined, geometrical, alternating between palettes of white and black. All except one.

Cutting through the divine coldness of the White Room like a sudden rush of blood to the heart, a red mid-length dress – the “La Fiesta” dress – made its way along the runway.

By the end of the show the hall was filled with rapturous applause. The Italian designer himself would later recall: “My mother said, ‘Do you hear them? They want you, because you did it, you won.’ Within an hour, they had bought the entire collection, and I was inundated with orders.”

The particular shade of red of the Fiesta dress, known still as “Rosso Valentino”, would become the literal fil rouge (red thread) of passion and heroic femininity weaving together Valentino’s artistic expression. It would even earn him his own Pantone shade by the code 2035C.

Valentino devoted his career to dressing women in red, always returning to the same principles: to honour their body instead of correcting it, to frame elegance as a form of empowerment and to dress the body so that the mind, too, may be reminded of its own innate agency. This was Valentino’s definition of beauty. This was what he meant when he said he knew what women wanted. And to pursue that endeavour consistently, unwaveringly, was his passion.

“Beauty has always been the pinnacle to which Valentino relentlessly aspired, a passion he could not do without,” wrote fashion journalist Elena Banfi in Vanity Fair. “And we are not just talking about red carpets or princess gowns, but the all-around beauty that permeated every moment of his life, flowing out of everything he did.”

Would it be possible for a young Valentino to flourish now? The conditions which allowed him to sustain his passion at the time are now being increasingly eroded by the demands of the market, dictated by speed, mass production and algorithmic optimisation.

“There has become an expectation to see the ‘new’ and ‘better’ in today’s industry, yet the value of craftmanship has been lost,” says William Loth, a young designer at La Fetiche, a fashion brand known for its sustainability and artisanal craftmanship. “The fashion industry has ultimately been blindsided by the convenience of fast fashion and people are willing to sacrifice quality and sustainability for instant gratification.

“Companies that release one or two collections a year (like Valentino) are far more credible than those who pump out new ranges of clothes every month. Slow fashion, for me, is the solution to sustaining my passion for clothes.”

For the Italian designer, too, passion was not about a sudden feeling, a rapid gush, a seasonal caprice. It was a sustained commitment at one’s own risk; a lifelong loyalty to the pursuit of empowerment and agency; a cumulative effort that would one day have people saying, as we do now: “I recognise this, this is Valentino.”