Deliberations about Kingston’s future building developments have been made concrete in the form of the borough’s first Urban Room.

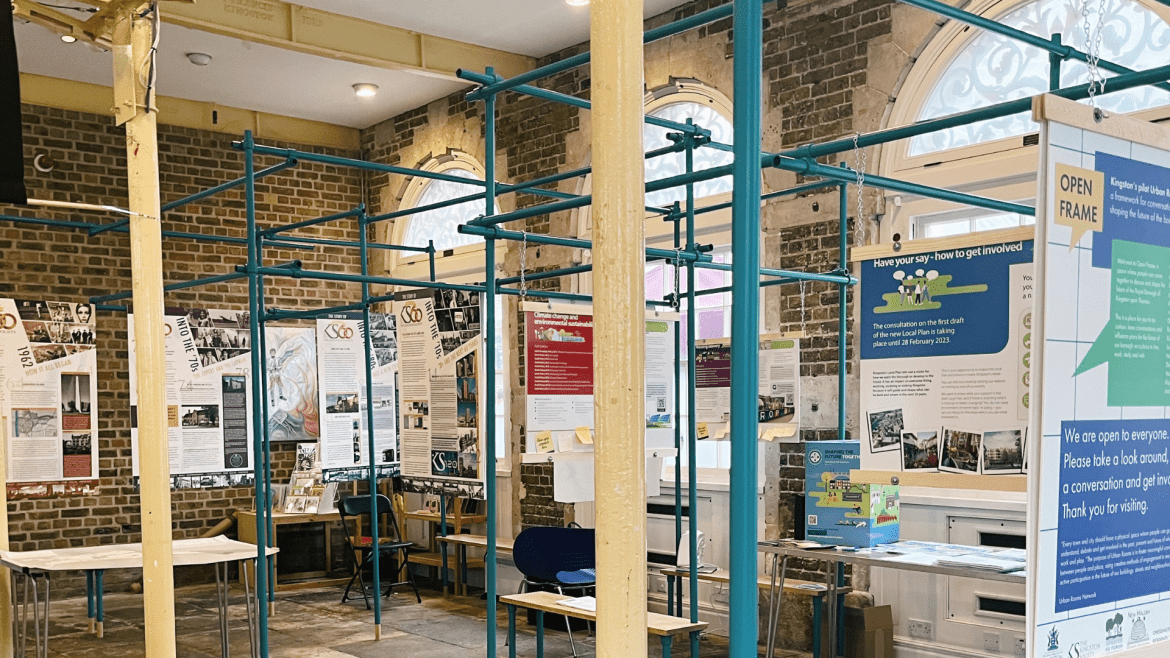

Hosted at Not My Beautiful House on Ancient Market Street since January 18, the Urban Room pilot aims to engage the public with the future of development in Kingston.

Urban Rooms are not a novel invention. Almost every city in Japan and China has a space which invites residents to participate in the design of the urban environment. There is no universal model for what an Urban Room looks like or how it functions, it is simply about encouraging local engagement with the structure of the town.

Croyden established its own Urban Room in 2020, focusing on making housing and infrastructure development plans more accessible to residents.

How it works

The concept of the Urban Room, coined by Sir Tim Farrel in his National Review of Architecture and the Built Environment (2014), was defined as a communal space in which locals can come together to debate the future of a neighbourhood.

The idea is to have an accessible space within a public environment, like a town centre, where residents can drop in and see what planning developments are being discussed in their area. It attempts to remove the confusing bureaucracy of council planning applications and allows the public to be more involved in the decision-making process by giving residents a voice.

Peter Karpinski, also a member of the urban planning and conservation group Kingston Society, has been leading the charge for the project. He said: “The Urban Room offers the chance to look at the way Kingston is and what it could be.”

Karpinski was working as a civil servant in the government at the time Farrel was conducting his report. He encouraged Farrel and his team to use an existing cross-country network of architecture centres. These centres were intended for improving management, design and construction of buildings.

Farrel stated in his report’s conclusion: “Every town and city without an architecture and built environment centre should have an ‘urban room’ where the past, present and future of that place can be inspected.”

Karpinski had petitioned for an Urban Room in Kingston for some time. “Then Covid-19 came along and I almost gave up,” he said.

In January 2021, Leaders North Kingston Neighbourhood Forum and Chessington District Residents’ Association came to Karpinski and urged him to take up his cause again.

A new plan for the borough

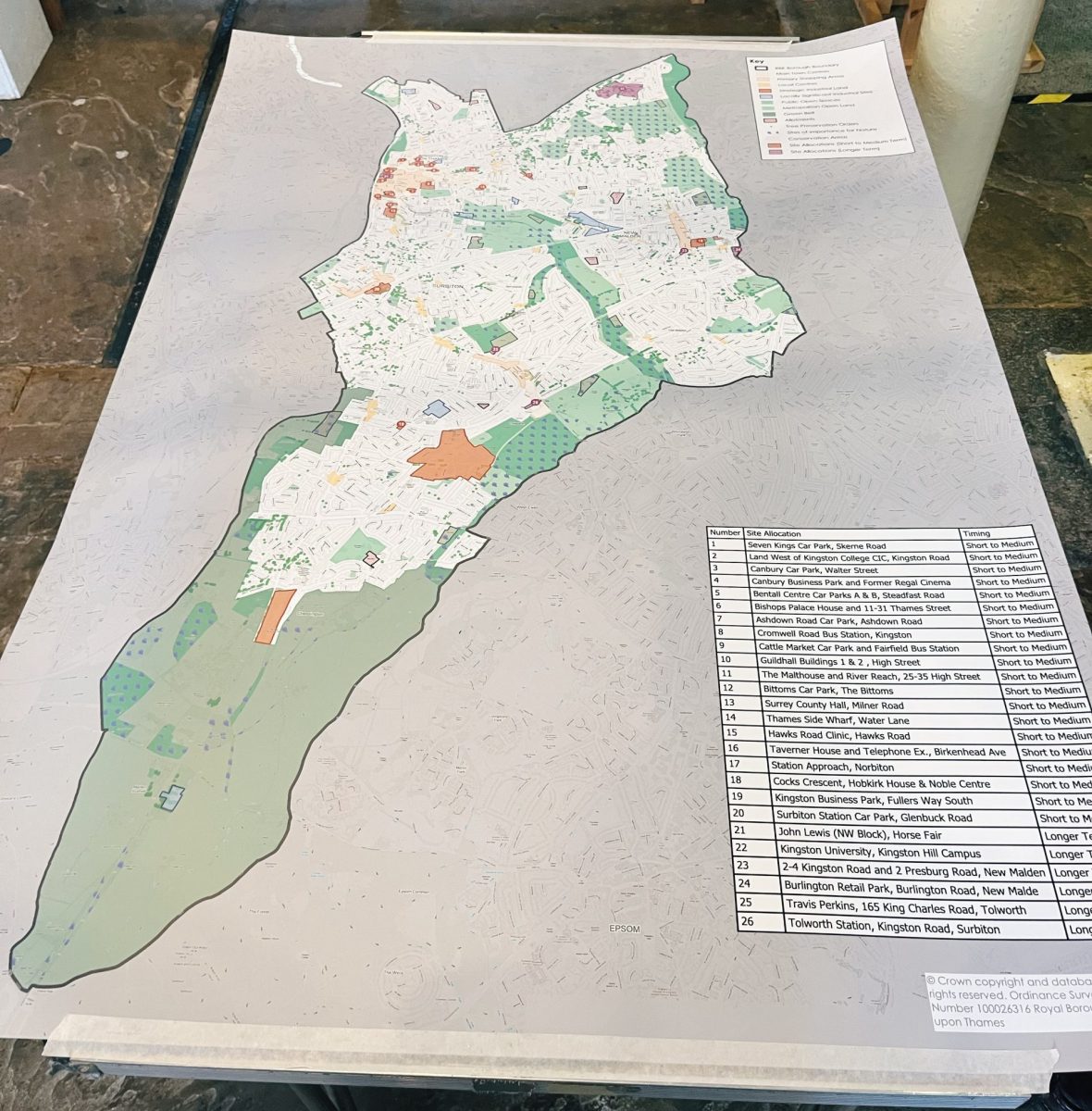

Kingston is also attempting to increase public participation with planning. The Local Plan, a document that guides the council on planning decisions and development for the next 20 years, has been exhibited in the Urban Room since its opening.

The Local Plan is generic by nature; according to the National Planning Policy Framework, the plan is aspirational in reflecting how the council want the area to look in the next 20 years. For Kingston, this could mean the amount of green spaces, the quantity and height of high-rise buildings, as well as the number and accessibility of transport links.

For instance, RBK want to maintain Kingston’s proud heritage of a market town while still driving regeneration in building and road developments. Kingston Society praises the council for wanting to conserve the character of the town but is concerned over the potential infringement of tall buildings up to 78-metres high in the town centre.

The new Local Plan replaces RBK’s 2012 Core Strategy for planning. Karpinski said: “Planning permission is being granted based on old guidelines, it’s just not representative of the world we live in.”

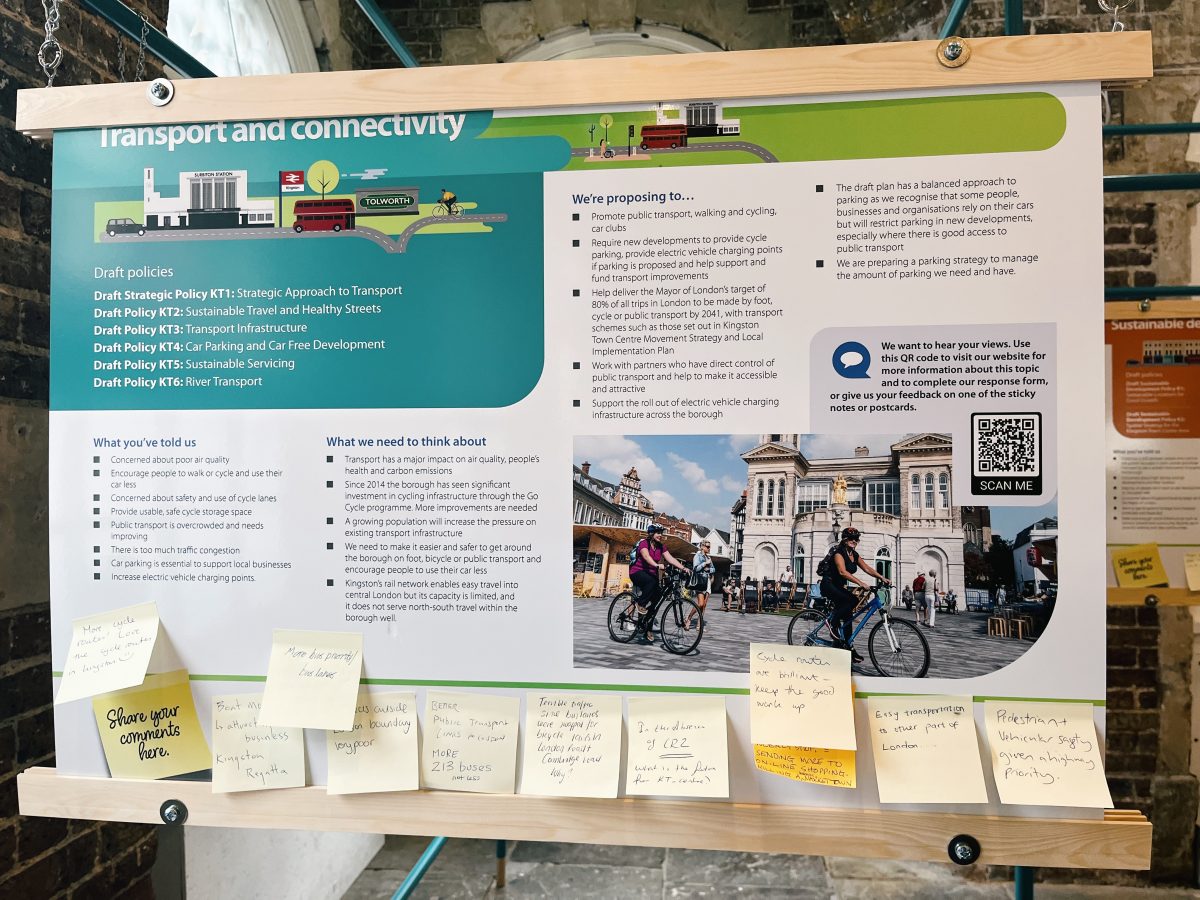

Emma Crowe, communications and engagement lead for RBK, said that the sweeping polices is the framework that future developers will be assessed on for their planning and developments requests. This affects residents’ transport in and around London, keeping businesses in the high street, obtaining sufficient number of quality housing, access to green spaces and more.

Crowe said: “If it’s not in here, it doesn’t go through. The Local Plan means we get the fundamentals right and get the right planning applications.”

Getting the younger generations involved

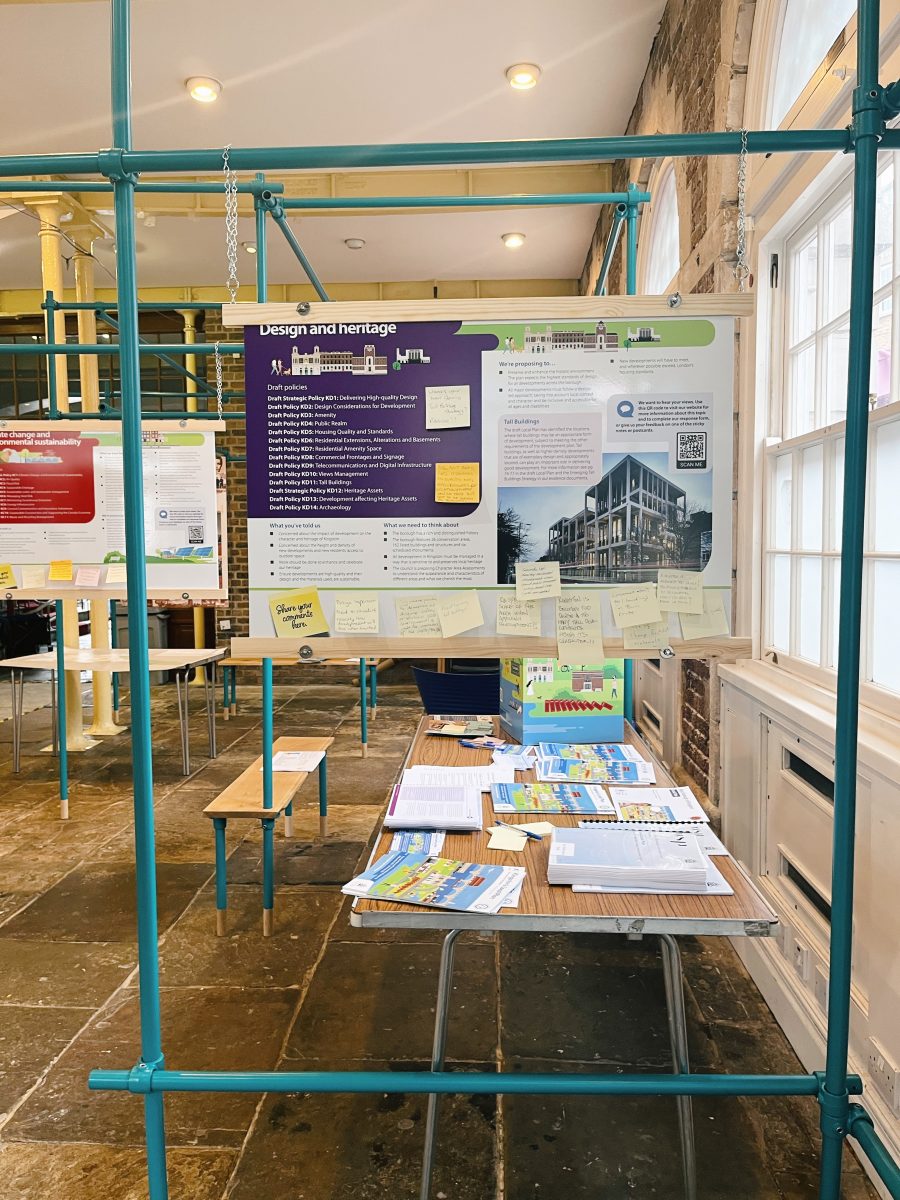

Placards of the key features of the Local Plan hang from turquoise steel frames. The structure was designed and constructed by 150 Kingston University students as part of a short-term consultancy initiative called The Vertical Project.

Visitors can write Post-It notes on overarching policy cards, read other people’s ideas and write on response cards. There is also a detailed survey online for residents to dig down into the effectiveness of the plan.

One month into the Urban Room’s pilot, the polices with the most engagement were transport and housing. Some Post-Its read “transport to outside London boundary very poor” and “pedestrian and vehicular safety given a higher priority”.

The council previously held three, demographically diverse, citizen panel workshops during the first draft of the local plan between March and October 2022.

In contrast to RBK’s citizen panels, Karpinski explained that the Urban Room is a neutral and safe space for public discussions. He said: “It is not backed by the council, not backed by the developers, we support the community here to have their say.”

Karpinski hopes that the Urban Room will be part of a long-term scheme that will be wheeled out to places such as New Malden, to be less Kingston-centric.

While Crowe could not commit to plans to roll out more Urban Rooms, she said: “In two years’ time, we want it to be an established as a familiar place where people can drop in and see what’s happening in Kingston.”

Karpinski said that what he really wants to see is the younger generation engage. He cited the climate emergency, building on the green belt, tall buildings and HS2 as problems for the future generations. “Decisions the old fogey are making will bite them,” Karpinski said.

The university-driven Vertical Project was one way to get young people involved. He noted that similar schemes have also run in Sheffield with its Urban Room, used for architectural teaching and research.

Admitting it is difficult to get people engaged with local development plans, Karpinski acknowledged that conversations can be “knotty” and it can be difficult to find solutions.

Ambitious but demanding plans

The Local Plan incorporates Sadiq Khan’s 2021’s London Plan. The council is currently under pressure by the Mayor of London to provide 9,000 new homes from the London Plan over the next 20-25 years.

According to the Strategic Housing Market Assessment (2016), over the past five years only 124 net additional new affordable homes have been built in the borough. That equates to approximately 25 new affordable homes per year. RBK admits to a waiting list of 3,459 needing social housing. Karpinski calculated, based on the current rate, that “it will take 139 years just to fill the existing waiting list for housing. It’s just awful.”

The emerging Local Plan will require developments for 10 or more residential units to provide at least 35% of new-build homes as affordable housing, and up to 50% on public sector land. The previous plan (2012) targeted 50% for social housing.

After declaring a climate emergency in 2019, RBK is pushing the borough towards being carbon neutral by 2030, while Kingston council is hoping to be zero-carbon by 2038.

Some of the policies go “above and beyond” the London Plan. For example, RBK wants every planning proposal to have a 30% increase in the ecological value of a site (such as protecting wildlife habitats and minimising pollution) in contrast to London’s 10%.

Roger Hayes, RBK’s portfolio holder for planning policy and community engagement, said that the council wants to hear residents’ thoughts on the local plan.

Hayes said: “We cannot achieve our much-needed goals through wishful thinking and hoping that it will somehow all just turn out OK. We want to…create a compelling 20-year vision of the place we all want to live, work, visit and study in. A place that understands and treasures its history, cares passionately about both its built and natural environment and is confident of its future.”

The Urban Room installation ends on February 28, with more revisions on the Local Plan taking place between March and April.

After more public examination in the summer and an inspector’s report, it will finally be adopted late 2023.

Want to read more on Kingston Society? Read: Kingston Society’s 60th anniversary celebrates the past, present and future challenges