Derek Osbourne is a man upon whom time – in more than one sense of the word – has left its mark. His beard, mainly black in the photographs taken at the time of his trial in 2013, has turned white in the space of three years.

A year in prison for possession and distribution of child pornography, followed by effective banishment from the political world he inhabited for 27 years, has left him isolated. The former Liberal Democrat councillor for Beverley ward, who also led Kingston Council for a decade, is understandably nervous about speaking to a journalist. This is the first interview Osbourne has given since his fall from grace.

But he believes it is time to speak out now. An internal investigation by Kingston Council into Osbourne’s conduct while in office as council leader has officially been underway since 2014, but no word has been made public on its progress. The long silence has bred widespread speculation, with rumours that Osbourne was not acting alone. Osbourne thinks enough is enough.

“Part of the initial concern was that there might be a ‘ring’ operating out of council offices,” he said. “There wasn’t and it shouldn’t be taking so long to announce that.”

“The investigation’s chief purpose has to be to reassure the public that the council’s integrity is intact. It’s important to act swiftly and decisively. But how can people be reassured when the inquiry is now in its third year?”

The council says it is simply being as thorough as possible to get the facts straight. Osbourne thinks the delay is local politics at its dirtiest. “My suspicion is that the Tories are delaying it so that they can release the report just before next year’s elections and stir up the issue again as ammunition against the Lib Dems,” he said. “I can’t think what else the reason could be for sitting on it for so long.”

The rumours that he was linked to a paedophile ring are perhaps unsurprising in a nation that has been gripped by allegations of high-level child abuse rings since 2012, when the Jimmy Savile scandal erupted. Following his arrest in June 2013, Osbourne pleaded guilty to possessing, making and distributing indecent images of children.

But Osbourne says that his criminal activities came from an addiction to progressively more extreme pornography that eventually consumed him and destroyed his career.

“I am not sexually attracted to children,” he said quietly but firmly. “You might not believe that. What happened was that I became addicted to porn. And once you are addicted, you become desensitized and get onto harder and harder stuff of all sorts.

“Yes, some of the images I looked at involved underage people. I looked at lots and lots of other things too. I’m still going through therapy for my addiction now, and the way it has been explained to me is that I had retreated into a fantasy world. Looking back, I can see that I was using porn to block out the stress I was under – I had already had a nervous breakdown in 2008. Pornography was a form of escapism to begin with but snowballed into something grotesque.”

How did the police catch him? “I started a blog and created a fantasy personality who was much worse than me, and that personality was the character of the blog. People would sign up to gain access to the stuff I posted and of course eventually one of them turned out to be a police officer,” he said.

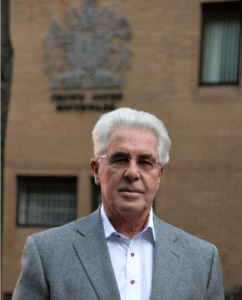

Credit: Rex Features

On the face of it, it seems hard to accept that there was a great difference between the person portrayed on the blog and the person who was writing that blog. The fact that novelists and authors do it all the time suggests Osbourne’s claim is not in itself implausible. But it was the accompanying photographs, described as ‘stomach churning’ by prosecutors, some involving people and animals, that were illegal and ultimately handcuffed Osbourne to his alter ego.

Unanswered questions

Osbourne appeared before his honour Judge Alistair McCreath, who has heard the cases of a number of high-profile sexual offenders. These have included ex-BBC disc jockey Chris Denning (now serving two sentences of 13 years each, for sex offences against underage boys), PR impresario Max Clifford (now serving eight years for sexual assaults on women), and Patrick Rock, aide to then-Prime Minister David Cameron (a 2016 suspended sentence for making and possessing indecent images of children).

Since Osbourne pleaded ‘guilty’ there was actually never a trial as such. The case went straight to sentencing and the public was spared the details. This has given rise to speculation. Perhaps the chief unresolved question is: What was Osbourne admitting to when he pleaded guilty to the offence of ‘making indecent images’?

“’Making’ includes downloading because each copy counts as a new creation. I’m not denying that there were photographs depicting sexual offences, and I hold my hands up because that’s bad enough. But I was not involved in any physical offences against anyone,” he said.

He says he is making good progress tackling his pornography addiction. “I am still going voluntarily through therapy. It’s expensive – £95 an hour, and that’s the unwaged rate – but it’s worthwhile. What has especially helped me is having a therapist I can reach out to when the going gets tough. It is good to speak to someone non-judgemental.”

But when he was released from prison in 2014, it was under a court order banning him from accessing interactive sex websites – and he breached that order in 2015 leading to rearrest and another court appearance before Alistair McCreath. Again, a guilty plea meant that the public didn’t learn very much. What happened?

“I wasn’t looking at anything illegal, I just ‘fell off the wagon’ but what I did wouldn’t be against the law for anyone else, which is why I only got a suspended sentence,” he said.

Prison and life after release

So, did a year’s ‘time’ served in prison have any deterrent effect on him in the end? This is the chapter in Osbourne’s life that has been completely closed to the public until now.

“Prison was very bad. The experience has completely changed my view of how we handle offenders in this country. Fair enough, I broke the law here and not elsewhere, but in Germany or Holland, for example, I would have been treated as a low-risk offender and given state-funded therapy. Which would have been the cheapest and most effective option.

“What does prison teach someone like me? Well, you don’t want to go back there, but that’s about it. Being kept in your cell for 21-22 hours a day isn’t a valuable experience. People go on about how prisons are like hotels. They know nothing. You might have a TV but it’ll only be a 12-inch screen and you have to hire it, which costs £1 a week and that’s a large amount for a prisoner. To show what I mean, I had a prison job as cleaner for a while, cleaning the bathroom areas, and my pay was £1.25 a day.”

Osbourne was held on remand at HMP Wandsworth and after sentencing became a low-risk Category ‘C’ inmate at HMP Brixton. “Brixton was very bad,” he recalls, “falling apart. We would spend a whole weekend without lighting, apart from emergency lights”. Finally he was transferred to Little Hey in Cambridgeshire as his release date approached.

Osbourne is quite definite that he was not the victim of an injustice. “I have no complaints about any stage of the process I went through, from arrest to trial. Everyone was very professional. But prison is grotesque and bizarre. When you force people together and give them nothing to do except find things in common with other prisoners, you are encouraging them to develop their existing forms of behaviour, not learn new ones.”

Life after release sounds as though it has been bleak. Predictably, Osbourne is unemployed and shunned by former colleagues. Just a few stalwart friends have stuck with him. But colour returns to Osbourne’s cheeks at last as he recounts instances of public support since his release.

“One thing that has really touched me has been the ordinary people who have given me support because of help I gave them when I was a councillor – helping them get rehoused or getting a disabled child into the right school for example. They know that I am more than my offence. They didn’t have to get in touch, but they did, just to show that they remembered me for positive reasons. It is some comfort to look back on having done good things that have made a difference for others.”

If there were to be a redemptive ‘second act’ to Osbourne’s public career – and at 63, he is hardly among the most senior figures in local civic life – his wealth of experience, personal as well as professional, could be of use to a body such as the Howard League for Penal Reform. But as the suspended sentence hanging over him demonstrates, Osbourne has yet to finally complete the most fundamental reform of all – that of himself.