The panic of money not stretching far enough is compounded by gig workers not having the same rights as regular salaried staff, new research by StandOut CV shows, exacerbating an already precarious job role.

The gig industry is made up of people paid for the completion of tasks rather than the time worked. On-demand jobs include drivers, couriers, freelance writers and, more recently, even lecturers.

On March 21, the takeaway delivery company Just Eat announced it was cutting 1,700 jobs and opting for gig economy workers instead.

The news comes despite the CEO of Just Eat, Jitse Groen, stating the gig economy has led to “precarious working conditions across Europe, the worst seen in 100 years.”

Standout CV, a recruitment advice platform, collated all the recent research on the UK gig economy (including government reports, journalist investigations and trade union research) and broke down the statistics.

According to StandOut CV 48% of gig workers in the UK also have a full-time job, using the money earned to support their income.

One of these gig workers is 31-year-old Leo Fitzpatrick whose full-time role is in publishing. Fitzpatrick has worked on and off as a Deliveroo bike courier since 2017, going through phases where he has used the food-delivery service as his primary source of income as well as a supplement in hard times.

Fitzpatrick told the Courier that his last shift was March 18 when he worked for two hours, doing five deliveries, and earning £22.59. The shift had a 1.2x boost, where drivers receive their average rate plus a small increase as it is a busy period.

Although £22.59 may not seem bad for two hours’ work, it equates to £3.765 per delivery.

“I wouldn’t log on if it wasn’t a boost,” he said. “The actual flat rate is such an insult and almost not worth logging on for.” He said the boost makes the wage up to £7 per hour- what Deliveroo used to pay riders in 2017.

Couriers for companies like Deliveroo work on an hourly basis, with a rate between £6-12 depending on the number of successful deliveries. At the time of Fitzpatrick’s last shift, the National Minimum Living wage for 23-year-olds and over was £9.50. It increased to £10.42 in April 2023. Any rate below £10 is paying less than the minimum wage, but the promise of added payment for every drop-off completed keeps an incentive.

“It will definitely affect the insecure workers Deliveroo provides,” Fitzpatrick said. “I can’t tell you the number of times I’ve said: ‘Right, that’s my last shift. I’m never ever doing this again.”

On March 16, Deliveroo reported a 14% revenue increase despite a challenging market. Although it has never posted a net profit figure, Deliveroo decreased its net loss from -£298m in 2021 to -£245m in 2022.

The Independent Workers of Great Britain Union reported in December 2022 that eight in 10 gig workers were pushed to cut their groceries and energy expenditure. In comparison to those in average salaried jobs surveyed by the Office for National Statistics (ONS), 35% workers reported they cut their spending in household essentials.

“Not knowing how much you’re going to have at the end of the week is just another precarious insecure situation,” Fitzpatrick said.

Poor working conditions

The definition of on-demand workers has come under legal scrutiny as companies like Uber claim their drivers are self-employed and therefore not entitled to sick-pay benefits and insurance.

Leigh Day, the law firm that represented Uber drivers in the Supreme Court February 2021 ruling that they should be entitled to workers’ rights, is working with Bolt and Addison Lee drivers to secure holiday pay and the National Living Wage.

Charlotte Pettman, representing Bolt for Leigh Day, said: “Once drivers have forked out their work-related expense on fuel and obtaining a private license, they are struggling to make ends meet.”

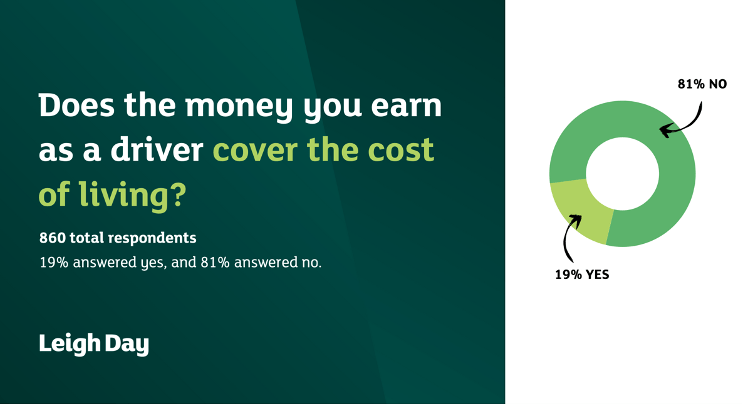

Leigh Day conducted a survey of 860 gig economy drivers and found that 81% did not think their wages covered the cost-of-living, with 73% of drivers stating they had worked more than six days without a day off.

Fitzpatrick, identifying with this struggle, said: “I have been needing to do more shifts than I have been doing for a long time just to make enough money.

“Drivers don’t have any negotiating power when entering into a contract and Bolt dictates the specific terms they work under,” Pettman said.

The conditions included rules of service, rate of pay and all communication made on behalf of the drivers to the customers.

Based on the drivers’ working relationship to Bolt, Pettman argued they should be recognised as workers.

A spokesperson for Bolt said: “Our extensive driver engagement shows this model is what the majority of drivers want […] if not, they will go elsewhere.”

Pettman said: “It’s a shame lessons haven’t been learnt from Uber and the supreme court judgement. These companies are benefiting by denying workers their rights.”

Fitzpatrick confirmed that many of the driver support systems are automated by machines. “You feel unprotected, like no one has your back.

“They’re not even willing to keep people hired to deal with the customer support and complaints.”

The tenuous definition and lack of legal status of the gig economy means officials find it difficult to legislate workers’ rights.

Responding to a Freedom of Information request in 2021, the ONS stated it does not collect specific data on gig economy workers.

In March 2022, the Mayor of London promised a Gig Economy Charter which would define the gig economy and establish best practise for on-demand workers by the end of 2022.

However, the charter has not yet materialised.

A spokesperson for the Mayor of London said the “new Charter for Good Work in the Gig Economy has been developed in consultation with partners and will be launched soon.”

More workers could lead to more exploitation

In March 2023, the number of people working at least once a week in the gig economy was 7.25 million people – 22.1% of the workforce – according to ONS data. This is approximately a 50% increase from 14.7% of the workforce in 2021, as researched by the University of Hertfordshire.

Global data survey revealed 14.5% of employees were considering taking a second job in 2023, with 14% of employees doing so in 2022.

In line with the current trend forecast, the gig economy is likely to continue to grow because of the convenience of the job and the increasing need for extra income because of the rising cost-of-living.

StandOut CV predicts that by 2026 the industry will have 14.86 million regular worker making up around 45.3% of the UK’s workforce.

Why does Fitzpatrick still work for Deliveroo if he feels exploited?

“At this point, I just consider exploitation a feature of the whole economic system,” he said. “It’s just how much you can bear.”