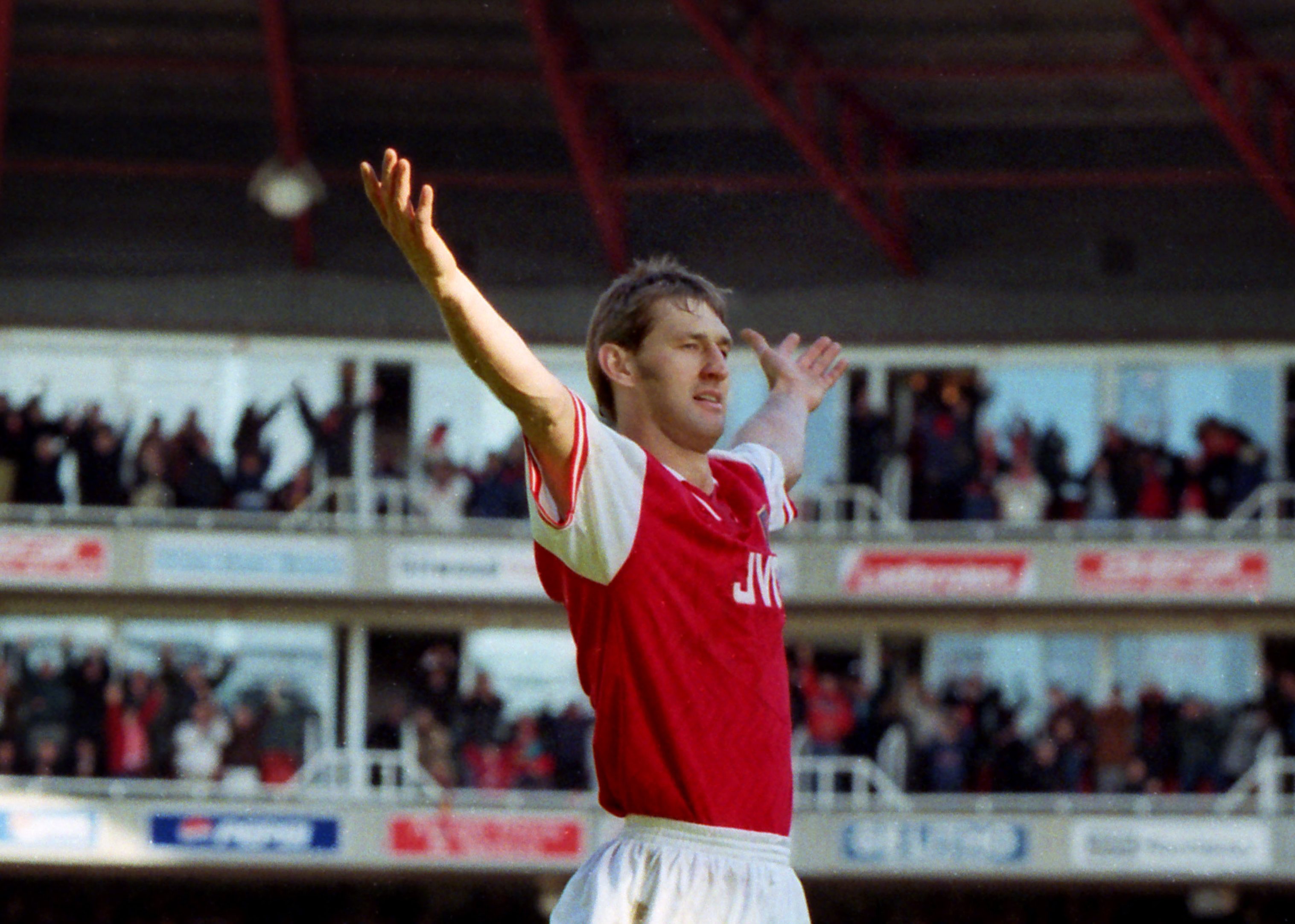

Tony Adams is a legend – a term oft-bandied about in a nation of pub-goers and lager downers, but one befitting the ex-Arsenal and England captain in more ways than one.

Not only has he achieved sufficient footballing honours to warrant genuine deity status – particularly among Arsenal supporters – but (more importantly, he might say) he has faced down his own demons and kicked a drinking habit that was, at one time, spiralling dangerously out of control.

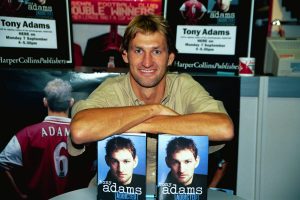

As alcohol awareness month (April) approaches and Adam’s eye-opening first autobiography Addicted nears its 20th anniversary, the Kingston Courier caught up with the celebrated centre-half to chat about his experiences at Alcoholics Anonymous (AA), his charity work at the Sporting Chance clinic and his thoughts on UK drinking culture.

“It was a long process of realisation and recovery,” said Adams of his alcoholism. “If you read the first chapter of Sober or Addicted – it’s all in there.”

Addicted and Sober refer to the titles of Adams’ two autobiographical books. Released 18 years apart, they provide a raw and candid insight into the life of a man locked in a tragic struggle with the bottle, who also just happened to captain his country in football.

“Go to an AA meeting to test the water”

And yet both contain stories that would be immediately recognisable to any alcoholic. “I would suggest that they go to an AA meeting to test the water – to see if they recognise themselves in what they hear,” said Adams, who revealed in his most recent book Sober that “AA meetings in Wimbledon and Putney kept me going”.

Of course, AA is not the only answer: Adams also cited “one-to-one therapy with a recovering addict” as having helped his recovery.

“Addiction is very complex and there are many facets to the disease and the [common] traits of alcoholics can be very similar,” he explained. “But this is only understood when the wall of denial has been destroyed.”

Describing an AA meeting, Adams said: “A group of drunks discuss their issues in a non-judgemental, mutually supportive room. And through identification and communion we all stay sober.”

An old hand at this recovery game by now, Adams quit in 1996, aged 29. At that time, English football still had a heavy drinking culture – Adams himself led marathon boozing sessions with his teammates every week, a tradition so infamous it has its own wikipedia page.

“Britain definitely suffered from a drinking culture (there is much more understanding of this nowadays, but it is still very much part of the British culture) when I started drinking,” said Adams.

“As I said, there is more understanding of the perils of alcoholism – and now sadly to this we also add gambling now. To help myself stay stopped, I changed my environment, I moved to the other side of London and only hung about with people in recovery.”

Of course, moving away from temptation can help, but alcoholism is not necessarily just a product of social environment. There is a well-documented link between alcoholism and other mental health disorders – depression, for example.

“Alcohol is a depressant”

“Of course it is linked, as addiction is about thoughts and feelings,” asserts Adams. “You can’t be an addict and not be depressed (alcohol is a depressant) lonely and scared. Addiction is a mental, emotional, disease.”

This is very much the approach of the charity Adams set up in 2000, with the proceeds of his first autobiography. The Sporting Chance Clinic offers services for problems with emotional health, alcohol, drugs, gambling and depression.

“I go in to this in my first book Addicted. I am very proud of my work at The Sporting Chance – which is now the biggest provider of mental and emotional support to the sporting industry: all people who have been or who are affiliated with sport in some way. I think there are things for students out there [as well]?”

Unfortunately football still seems to be struggling with the issue of mental health. Scottish League Two player Daniel Cox revealed he was mocked and taunted on-field after speaking out about his mental health struggles.

“Addiction still has a lot of stigma”

“Mental health is more acceptable and spoken about now which is great, but addiction still has a lot of stigma around it unfortunately: people can still think of it as self-inflicted rather than as a mental disease. We tackle it best by putting it into the same arena as mental and emotional illness.”

At a time when footballers are tentatively starting to open up about their mental health, from Stan Collymore to Danny Rose, a voice like Adam’s – one of the first to ‘come out’, as it were – does lend a certain poise and authority to the much-misunderstood topic.

“Easy does it,” said the veteran defender to end our interview. It seemed almost a Freudian slip from a man still coming to terms with an uneasy past.

But as mantras go, you could certainly do worse.